Psi

Menu

III - THE INTERVIEWS

Chapter 14

Robert Kane: The Libertarian Free-Willer (Jan 2015)

Robert Kane: The Libertarian Free-Willer (Jan 2015)

|

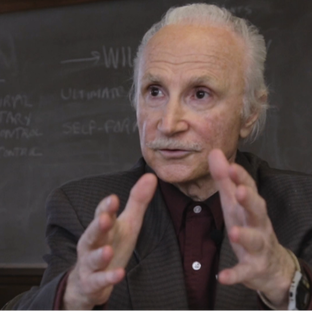

After meeting Coricelli and Gazzaniga in LA, I traveled across the US in January 2015 to meet with the other experts who had agreed to an interview. On the 25th, I flew to Austin to meet with Robert Kane, who is Distinguished Teaching Professor of Philosophy at the University of Texas at Austin. Kane is considered to be the leading libertarian philosopher on the subject of free will, and is the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Free Will, widely used in university philosophy classes.

To understand where Kane stands in the free will debate, it will be useful here to explain briefly what the big difficulty surrounding free will really is and why it is still today, after centuries of philosophizing, a hot topic. This will also serve to situate the other philosophers I interviewed on the spectrum and bring out their relative positions and disagreements. As I mentioned, Kane is a libertarian; this means he considers that free will is not compatible with determinism. He concedes that we are undeniably determined by many things which are out of our control (our genes, our neurons, our environment, etc.), but that what really matters is that we be ultimately responsible for who we are, such that when we act freely, we are acting on a will of our own free making. What this means is that, some (if not most) of our decisions may indeed be entirely determined, but what matters is that at some points in our past, there were some decisions that were undetermined, sufficiently so that, through them, we can be said to have formed the will upon which we are now acting. To illustrate this, Kane quotes Aristotle who puts it perfectly: “If a man is responsible for the wicked acts that flow from his character, he must at some time in the past have been responsible for forming the wicked character from which these acts flow.”

Many philosophers believe that this is impossible, because the causal nature of the universe, whatever it is, doesn’t allow for it. This resistance is often called the “Standard Argument” against free will, and it goes like this:

|

|

Kane has spent over forty years fighting the Standard Argument, and I must say I admire the consistency with which he has built up his theoretical edifice, as well as the energy with which he defends it. First of all, here is how he introduces the randomness into things (which is necessary at some point to defend libertarian free will): quantum random events at a tiny scale in our brain (perhaps in the synapses) cause tiny micro-variations, the effects of which are amplified through chaotic processes in the brain, thus leading to potentially different outcomes down the road. According to him, there are particular moments in life when we face a decision of such importance, where the competing options are both supported by non-conclusive but equally strong reasons, that we are “in two minds” and torn about what to do. In these “soul-searching moments,” we must make an effort to resolve the tension and make a choice.

Kane claims that the effort made to simultaneously “parallel process” the deliberation in favor of both (or all) competing options creates noise in the brain, stirring up quantum indeterminacies at the neuronal level and thus screening off complete determination from the past. The thoughts that feed the deliberation will thus to some degree appear randomly (rather, the probability that any given thought among all the available and potential thoughts in our brain will emerge or become conscious will be more or less high) and in the end, the decision we make, while fundamentally hinging on random brain-events, is nonetheless one we intentionally will for our own reasons, one for which we can therefore be said to be ultimately responsible for – and this holds either way, whatever choice we end up making, because in every case we had good reasons for doing so and we intentionally willed to do so. Kane calls these moments “self-forming actions,” because they serve to form who we become afterwards, and crucially, they are moments which are “will-setting” – meaning that up until the moment we made the choice, our will was not settled – it was truly undetermined. It is by virtue of making the choice that we set it. And these self-forming actions are therefore those actions by which we become ultimately responsible for who we are.

Of course, Kane has faced many challenges to his model – mostly from determinists – and they require many books to be fully covered. It is no coincidence that Kane’s interview was the one that lasted the longest (he spoke with me for almost 3 hours). I was actually surprised how eagerly he had prepared for the interview and also how open he was to telling his own personal experience, including the story of his eldest son who suffered from schizophrenia and died in his late twenties. After our conversation, Kane toured me around Austin and took me out for a huge Texan barbecue, most of which returned to his wife in a doggy-bag. One amusing anecdote in our conversation was that one of my filmmaking heroes, Richard Linklater, a local Austinite, had studied in Kane’s philosophy department and even shot some of his films there, with the participation of some of Kane’s colleagues.

|