Psi

Menu

PART III - THE INTERVIEWS

Chapter 19

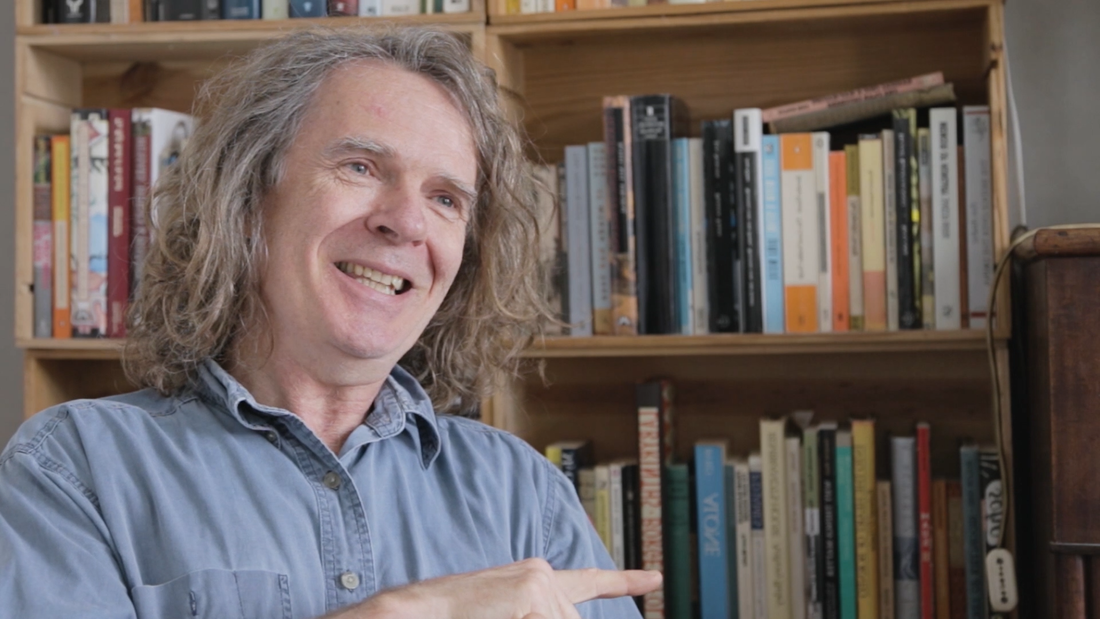

Galen Strawson: The Happy Determinist (Feb 2015)

Galen Strawson: The Happy Determinist (Feb 2015)

|

After my stay in Boston, I returned to Paris and then arranged to meet in London with British philosopher Galen Strawson, who happens to be a colleague of Robert Kane at the University of Texas at Austin, only he wasn’t there during my earlier visit. On the free will debate, Strawson is often categorized as a “hard determinist,” which means that he is essentially a tenant of the Standard Argument against free will: whether the world is deterministic or indeterministic, ultimate responsibility for our acts is impossible, seeing as we are either entirely caused or entirely subject to chance (and so, in the end, the libertarian kind of free will, which is the one he agrees we are really after, is not possible). At the same time, inheriting the ideas of his father, P. F. Strawson, also a prominent philosopher, he claims that the feeling of free will, perhaps akin to an emotion, and more importantly the first person experience of agency is not only unlikely to go away even if determinism were proven to be true, but practically useful for psychological well-being and social cohesion.

Aside from writing about free will and determinism, Strawson has also worked on another very interesting subject: narrativity. This is a theory in psychology that claims that most people are “narrative” beings, meaning that they construct a single story that covers their whole life and they feel like the protagonist of that story. Furthermore, narrativity makes the normative claim that people ought to be narrative in order to be happy and that not being narrative is in some way detrimental to one’s well-being.

Strawson has spoken out against both premises, claiming that the empirical claim is overstated – not everyone is narrative and there is probably a much more nuanced spectrum of how people relate to their selves and their past – and that the normative one is plainly wrong: you can absolutely be happy without being narrative. To specify his point, Strawson distinguishes “diachronic” people whose sense of self is greatly integrated into the broader story of their life and “episodic” people whose sense of self is far more concentrated in the present with less connection to their past and future selves. While preparing for the interview with Strawson, I realized why I was drawn to this aspect of his work: I recognized myself as being a rather “episodic” person who wishes to be more “diachronic” – in other words, my life doesn't feel as coherent and singular as I would like it to be. At one point during the interview, Strawson offered a personal example to which I immediately related; he said: “I remember when I visited Petra in 1972. I remember the scenes, the visuals… But I’m not there. I’m just the camera.” This was eerily similar to how I feel about many different moments in my past. For instance, I perfectly remember the time I worked as a flight attendant in my early twenties: going to the staff quarters of the Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris, prepping for flights, working on board planes, visiting new countries, etc. But when I think of all this, I wasn’t there. I have a good “objective” memory of these things - in the sense of factual, autobiographical - but I have little “subjective” memory of them. It is as though they have all become “void” snapshots; in fact, the actual pictures which I took on these trips have become the first things that come to mind when I think of these memories. Perhaps most people feel the same, I’m not sure. All I know this is something that bothers me, whereas Strawson doesn’t seem to mind. And I wanted to know why.

In June 2014, I was also fortunate enough to visit Petra and this is an experience to which I am still very connected, cognitively speaking. When I think of it, I was definitely there. It feels mine, still. And so the important question for me to sort out is whether the strength of my cognitive connection to past experiences is a function of time; in other words, is it just a matter of time before my trip to Petra feels, to future me, like an experience enjoyed by a different past me? Or is there something else which could account for the disconnect?

|

|

I believe I partly have an answer to this. First of all, time does play a role - we naturally feel closer to experiences that just happened than to those long past. But I don’t think time is a sufficient force to break the connection, it can only weaken it. If I look at my own past, I believe the main reason for the subjective disconnection is the lack of objective coherence and continuity to my past life itself.

I spoke earlier of Gazzaniga’s “interpreter module” in the left brain, the function of which is to tie all experiences together and construct the story of our lives. In other words, the “interpreter module” is probably the “narrator” underlying narrativity. To do its job, maybe the interpreter requires a degree of “objective” consistency (i.e. a consistency in living situations, social surroundings, ambitions, projects, etc.) without which it struggles to provide a sufficiently good thread to create “subjective” consistency. And indeed, the subjective disconnect I feel to my past is most salient with regards to objectively disconnected periods of my life, which has indeed been made up of a patchwork of endeavors with little consistency, all lasting anywhere between 1 and 5 years, and all very self-contained: a different city, a different occupation, a different immediate goal, a different parental situation, a different girlfriend and different friend groups. Perhaps my interpreter module is simply struggling to explain it in any coherent sense, and consequently, the more “objectively” isolated or removed from the present a period of my life is, the harder it is to fit into any coherent “subjective” story linked with who I am today. Going forward, I believe the key to keeping the connection with the past is twofold: first, relationships. The only source of cognitive connection I still have with the episodes of my life which I feel removed from is through family and friends, because they act as external anchors that lock you into your continuing self and provide a thread to connect the beads. And secondly, having more “objective” consistency to life, and this can only happen when you have found “your path,” in other words when what you are doing is coherent with your long-term ambition for becoming who you want to be. This supposes you know who you want to become, which can itself be a long, meandering stumble. Today, I believe I have now found the path which is right for me.

|