Psi

Menu

I - PRE-PRODUCTION

(Sept 2013 - March 2014)

(Sept 2013 - March 2014)

Chapter 1

The Beginning: How I Came to Make This Film

The Beginning: How I Came to Make This Film

|

After spending New Years of 2014 in Copenhagen with some friends, I returned to my tiny chambre de bonne in Paris with a severe hangover and no resolutions made. At the time, I was studying at La Sorbonne University, pursuing a Master’s degrees in International Relations and another one in Philosophy. I had perhaps been academically greedy. Both were demanding and I was facing a double-dose of second semester classes and two different dissertations to write by the end of the summer. If I worked hard enough, I would hopefully be able to chose one avenue to continue on with a PhD. I had a preference for philosophy, but international relations would be the more sensible choice, professionally speaking.

How had this happened? How was it that, ever since I was a kid, I wanted to be a filmmaker and yet here I was, pouring all my energy into becoming an academic in political science or contemporary ethics? I felt like the past 8 years of my life, I had been coasting half-asleep on a highway and had completely lost focus of where I wanted to be going – a bit like my drive back from Copenhagen. A change of direction was needed. Urgently. 27, time to get moving...

Another thing was setting off this existential alarm-bell: a few months later, on March 4th, I was going to turn 27. That’s a tricky age. It’s the kind of age where if you say you’re still “searching for yourself,” people start looking at you a bit funny, as though they couldn’t decide whether to empathize with you or loath you a little bit. Plus, having read the Wikipedia biographies of most filmmakers I admire, I was acutely aware that approximately between the ages of 26 and 32, most of them released their first major film. Paul Thomas Anderson was 26 when he made Hard Eight and 27 when he made Boogie Nights; Jason Reitman, 28 when he made Thank you for smoking; Darren Aronofsky and Guillaume Canet were both 29 when they made Pi and Mon idole respectively; while Christopher Nolan had made Following and Memento by the time he was 30, an age at which Guy Ritchie made Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. This, of course, is discounting freaks like Xavier Dolan, who can make any aspiring filmmaker born before 1989 feel inadequate.

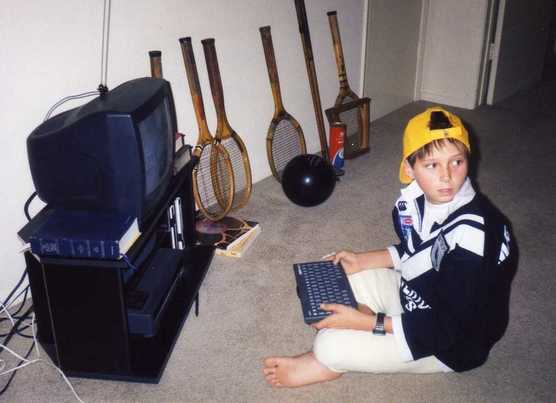

On January 3, I made a decision: I need to do something in order to steer my life back in the direction of filmmaking. I had a feature screenplay written and a ton of other film ideas to write, but hardly any directorial experience. So if I was ever going to find a production company that would not only be interested in buying my screenplays but also taking me on as the director, I had to be more than a guy with a couple of good stories. I had to have some experience directing. I had to shoot something. Obviously, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. At first, this was more of a strategic move: I needed to shoot something that looked good and that would be like a calling card anytime I sent out my screenplays. I thought I’d spend about a 6-to-12 months working on it, and have a decent 6-to-12 minute short that would showcase my potential. At the same time, I was also really itching to get my hands on a camera and shoot something. I had typed on keyboards almost every day since I was a teenager, but I hadn’t looked through a lens for years and I missed it. I love motion picture. Always have. When I was a kid and I played with my toys, I used to make up action sequences that I would play and replay, each time repositioning my head like I would move a camera, looking for the best viewing angle – and once I had designed a good sequence, I would play the action for myself as though I was watching a movie. Don't know why, but the aesthetic quality of moving bodies and action has always given me great pleasure and driven this desire to capture it in a repeatable way. Childhood dream

|

|

As a teenager, this desire to create things shifted away from toys and moved towards writing. I knew that my brain was wired in such a way that ideas would pop into my mind and develop into stories. Maybe everyone's brain is the same, but my introversion and desire to entertain (both parents and friends) gave me the will and time to develop them in the secrecy of my bedroom. Over the years, I jotted down hundreds of concepts for films, some of which were really stupid and have since been abandoned, others which have stood the test of time and are still in the queue.

My parents divorced when I was 12 and from then on I kept to myself a lot, spending most of my evenings writing. I don’t think the divorce caused any sort of trauma that fueled my need to write, but what it did do was give me a lot of time and independence. With no family unit, I was doing my own thing most of the time, and because I was a sensible kid with good school grades, my parents pretty much let me take care of myself in terms of managing for work and leisure. |

|

|

As a kid, most of my free time was spent writing. And because at that age there isn’t much at stake yet, I could easily manage school work and my writing. School was like this continuous, day-to-day chore that would end there if satisfied, but was clearly second on my priority list. As I grew older, though, studies inevitably became a bigger and more future-oriented part of life, and so the choice of where to allot time and effort became more consequential: should I develop my creative streak and pursue a risky artistic life, or use my brains and get a solid career in a secure field?

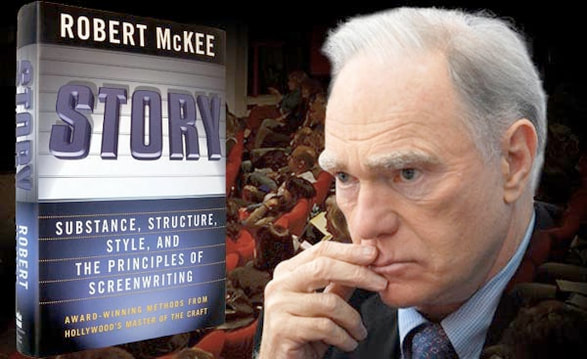

Fittingly, the split between my parents embodied in some ways this dilemma: on one hand my father was pushing me to prepare to be a filmmaker as though it was just a matter of time and there was nothing to worry about, and on the other my mother kept reminding me that most filmmakers aren’t making creatively-fulfilling millions in Hollywood but chasing paychecks doing commercial gigs they resent. Throughout my teen years, my father wanted me to get a head start: he bought me tons of books on filmmaking and sent me several times to the screenwriting seminars of Hollywood guru Robert McKee. Many people criticize his seminars for their formulaic appearances, but I found them to be incredibly inspiring, probably because of my young age. I was 14 the first time I attended his “Story” seminar and so I wasn’t there with any particular pressure. The big takeaway for me was really that screenwriting is a craft with rules that must be known and mastered (if only to expand on them and break them), a craft that requires a lot of determination, patience, discipline and suffering too. It instilled in me an admiration for good character and plot design, and yet, because I hadn’t been to his seminars like a student going to class or an author struggling with writer’s block, I didn’t feel bound by his teachings – which is why I have written things that would surely get a beating if he were to review them. |

|

Teenage goal

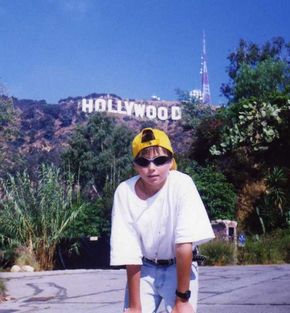

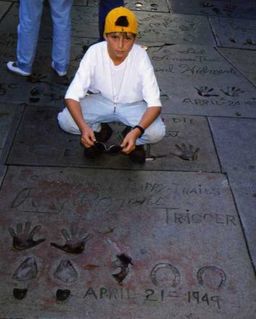

Throughout middle school and high-school, unlike most of my classmates who had no idea really what to expect in the adult world or what to answer to the question “tu veux faire quoi quand tu seras grand?” (French for: “what do you want to do when you grow up?”), I never had a doubt: I was going to become a filmmaker and I was going to go and study and work in Hollywood. This unwavering belief had a great impact on my formative teen years – but mostly in a negative way.

The first decision this had a bearing on came with the choice of specialty in high-school. Back in 2005, when you turned 16 in high-school in France, you had to choose a specialty track in which you would graduate from high-school: S (for Scientific), L (for Literary) and ES (for Economic & Social Sciences). You’d hope that they were all in equal standing, each preparing the best in their respective fields, but truth is, S was for the smart kids (the one that “opens all doors” as they said), ES was for those not good enough to get into S, and L was for the rest, the poets and the stoners. Each restricted a little more the options for further studies and of course, further down the line, for job opportunities. This system has been reformed now. But for me, when the time came for me to choose, I was offered a spot in S, but instead I chose L because I thought that this was more in tune with my desire to be a screenwriter. What use was math going to be to me anyways? My math teacher and my literature teacher argued over my case, the former claiming it was irresponsible of the latter to encourage me to prioritize the arts over science. Looking back on it now with my adult brain, I wish I had had more sense. The bright side of choosing L is that it led me to meet Aline-Florence Manent, who had also rebuffed S to choose L. We quickly became best friends throughout high-school. She and I once teamed up on a semester-long project called TPE (Travaux Personnels Encadrés). Aline came up with the subject: “Utopia & Architecture.” While she provided the philosophical underpinnings and architectural insights, I designed the presentation using my filmmaking and editing skills. I took my Hi-8 Sony Camcorder and shot footage of a building by French architect Le Cordbusier in Rezé, a suburb of Nantes about an hour away from where we lived, and edited it to Antonin Dvorjak’s New World symphony. The building, called “La cite radieuse” (“The radiant city”) had been designed as an urban embodiment of a utopia.

|

|

Extract of high school Video on "Le Cité Radieuse" (2004)

We nailed our presentation: the teacher gave Aline a 20/20 grade. I got a 19/20. I remember that I felt gutted. Like in the study where two chimps perform the same task but one gets rewarded with a raisin and the other with a rock, and the one who gets a rock throws a tantrum. At the time, my chimp brain was not happy, but in time I came to see that actually, I had been lucky: Aline was the master of that operation, I was just the nerd with a camcorder and a computer with editing software. Back then, I had little interest in philosophy and even less in architecture, so I remember finding the subject pretty pretentious actually. It’s amusing to me now, thinking back on this small project. Since then, of course, I have developed a love of philosophy and an interest in architecture. Psi is kind-of like my high-school project on steroids. I guess it took my brain a few more years than it did Aline’s to appreciate the substance as much as the form, but the seeds were already there. Perhaps she planted them.

It's also in high-school that I met two of my closest friends who would later come to play major parts in Psi: Thom Lefèvre, who plays in the London life and helped tremendously throughout the whole project, and Paul Marinucci, who plays in the Helsinki life and produced some of the project's music. |

|

For everyone, the high-school years are those where everything ahead is still possible. All major life-decisions are yet to be made. And when I do think about that period of my life, I think of Aline a lot, because, while she was the person who was the most like me, there was one crucial difference between us: she had been much smarter and receptive of advice than I had about what was to come. And it paid off: after getting the Baccalaureate, she went to Science Po Paris, then La Sorbonne, then ENS, then Harvard, where she recently finished her PhD in political history. And a bit shamefully, whenever I question my past, I always look at her as a beacon for a path I didn’t take and think, “If she did it, I could have done it too. If I had prepared myself in the same way, if I had worked just as much as she did, I, too, could have done a PhD at Harvard.” I don’t like catching myself thinking like this, because it reveals a weird fascination of mine with elite universities… and more importantly, it’s complete fantasy and quite probably wrong. It’s basically saying: “If I had been a different person then, I would be a different person now.”

For me, throughout high-school I was so certain of becoming a filmmaker in Hollywood that I never considered any alternative paths. Every time our teachers gave us presentations about universities and careers, I would ignore them. I was so confident that I didn’t need this information that I would either skip the meeting or sit in the corner working on a story. When I left high-school, I had paid so little attention and given it so little thought, I didn’t know how the University system worked, didn’t know the difference between prep-schools and Colleges and Grandes écoles, didn’t understand the difference between public and private schools, had no idea how scholarships and public grants worked. I came out of high-school just about as prepared for the adult world as a 12 year-old.

My problem here was compounded by the fact that France is an extremely diploma-driven society. Your success in life depends greatly on the coherence of your academic path. Consequently, there is tremendous pressure on high-schoolers to decide, by the time they are 18, what career they wish to have for the rest of their life, in order to start off on the right academic path from the get-go - what the French call “la voie royale”, meaning “royal path.” Deviating from it comes at the cost of some explicit professional prejudice as well as some unspoken social stigma. The big question I mentioned before was routinely asked in more adult terms: “Qu’est ce que tu vas faire de ta vie?” (“What are you gonna do with your life?”). Of course, I had my ready-made answer: “I’m gonna be a filmmaker!” While most adults quietly patronized my confidence, my peers were mostly envious of it, because many didn't have the slightest clue - they just knew they were going to follow the "most viable" path they could get into, apply themselves and climb the ladder as high as possible. Which meant, however, that they listened to those giving them navigation tips. Looking back on it now, I find it quite a tall order to expect 18-year-olds to confidently answer such a life-determining question given their lack of real life experience, especially when the system is not built to allow those who aren’t sure to figure it out. In France, barring prep-schools (which themselves are high-level schools designed to get you into higher specialized elite schools), you usually start your career education at 18. You start law school, or med school, or business school, when you’re 18. Unsurprisingly, the pressure is immense and the potential for mistake and, down the road, for frustration, failure and disappointment is equally great, because once you have chosen a path, it’s extremely difficult to change. Any academic switch on a CV is always seen as the sign of some kind of weakness of will, or muddiness of vision, and points to some necessary lack of knowledge and experience relative to other same-aged people who didn’t switch lanes. While to some extent this may be the case in other western countries, there are places where it is mitigated; in the USA, for instance, undergraduates go to College precisely to figure out what they want to do, spending four years testing courses and disciplines before starting law school or med-school. To the French, this would seem like four years wasted on dilly-dallying. In my case, the summer after high-school, my father left France and with him went my plan of film school in the USA. My confidence in my future rested wholly on his assurances that it was guaranteed and when the time came for it to happen, I learnt that the money was not there and that I should have been better prepared. I had obviously been too naïve, not taking charge of things earlier for myself, but until that point I had focused on school and writing and not dealt with what came afterwards. So when I realized I wasn’t actually going to Hollywood, I had to grow up fast and improvise. I was like one of those cartoon characters who overruns the edge of a cliff and only realizes it when he’s in mid-air. The only possible option in my mind was still film school, but this time in Paris. So, in the summer of 2005, I enrolled in a private (read expensive) film school in Paris, called EICAR. This was the closest branch I could cling onto.

First: Film School

Although at first I was relieved to have been able to keep my plan alive, I quickly discovered that film school wasn’t going to be for me. For one, it was too expensive - I had been greatly fortunate that my mother and grand-mother had lent me money to pay for the first year, but I didn't want to keep relying on their support for the second and third years and refused to take out a bank loan. I could have taken a job on the side, but midway through that first year, I started to reconsider the whole thing.

I was finding the general environment of film school rather counter-productive. For one, film school is not an environment for someone who, like me, has never been a huge film-buff. And in film school, I found myself surrounded by supreme film nerds, people who had either seen every Godard film or who thought that seeing every Godard film was necessary to become a good filmmaker. And the obsessive extent of knowledge that film schools demand and that students expect from each other is completely unnecessary, unrealistic and often tinted with a hint of smelling-your-own-fart snobbery. This directly played into the second reason I disliked film school: it was extremely insular, intellectually speaking. I was surrounded by people who lived in a world of cinema, 24/7. At school we would study cinema, after school we’d watch movies, after that we’d talk about them and the next day we’d be back in class analyzing films and the cycle would continue. Inevitably, I felt like all we produced at school were clichés. This was the first seed of an ever-growing conviction that if I wanted to tell original and engaging stories, I had get out of the film world and live other things. This sentiment was brought to the fore one night when I had dinner with Aline and some of her friends from Science Po. They were discussing social issues and politics - one of them who was the son of a Silicon Valley entrepreneur announced the impending arrival in Europe of a new Internet application that would revolutionize the way we view content, called YouTube. I was skeptical. But I realized that in only a few months since leaving high-school, the gap between Aline and me had become huge. I was a kid at the grown up’s table. I left that dinner wanting to be able to hold my own in a conversation about other things than the box office or what kind of mandarin works best.

Around that time I came to seriously question the whole point of filmmaking itself, and the more time I spent in film school, the more disenchanted with it I became. This feeling was compounded by the fact that in 2005, a wave of riots broke out in the northern suburbs of Paris – right where I was living. These riots confronted me with social, economic and political realities that made our little cocoon of expensive artistic struggles feel grotesque. Towards the end of the academic year, I remember having a one-on-one meeting with the head of my department, Jeffrey Goldberg, and asking him: if a calamity struck mankind, what kind of activities would we stop doing first and which ones would we uphold? I could tell from his beaten shrug that he couldn't save me from my disillusionment: sure, in the grand scheme of things, what we were doing here was pretty low-priority. Film is at best an intellectual stimulant, but mostly just entertainment. It is totally dispensable. Looking at my school, at my teachers, at my classmates, I felt like we were all clowns, selfish in wanting to do this for a living while most others worked hard keeping society running, doing jobs they didn’t necessarily chose or even like. I convinced myself that cinema is a privilege of the comfortable. Spielberg, one of my personal heroes, was only celebrated because we have a society that’s functioning correctly. Without doctors and law-makers and entrepreneurs and administrators, Spielberg would either not exist, or would be someone we would collectively loath as a misuse of funds. This cynicism would disappear later, as I’ll explain; but during that conversation with my teacher, I realized that I would be leaving film school at the end of the first year. There were some positives to film school of course. Two mainly. The first was the people I met and the friends I made. Being in the International section, I was surrounded by people from around the world - Cyprus, Belgium, Iceland, Israel, the US, Canada, Mexico - who all had a love of films and were each, in their own respect, figuring out who they wanted to be in life. Many of those are still good friends to this day. Most of them didn't go on to work in films, but a few did - one is a professional film editor in Cyprus, another a very experienced gaffer in Paris, another recently released her debut feature at Sundance.

The second advantage, was the ability to shoot - to just get your hands on the gear. Good film schools are those that operate like small film studios where students get to try out being several different positions and learn by doing, hands-on. I tried to make the most of those opportunities during my year there, shooting a few spec adverts. |

|

1st year project

Second: Law School

After my first year in film school, what I had been secretly looking into as a plan B to film school quickly became my new plan A: after completing my first year in film school, I enrolled in Paris’s most demanding law school, Université Panthéon-Assas. This was a radical change of pace. I found myself studying French law, European law as well as English and American common law. For the next few years, I became a typical university student in Paris, going to class, reading books, writing papers, preparing presentations, studying for midterms, being nervous about grades and, of course, wasting days in cafés and nights in bistros. After two years of law school, I shifted gears and got a Bachelor’s in Political Science. This initial 3-year run of University gave me a general grasp on how the world functions politically, but I still felt like I needed more tools to go beyond that and question it. This originally led to my interest in philosophy. A couple years later, I moved to England and studied ethics at King’s College London, before then returning yet a few years later to Paris to do research in contemporary philosophy and international relations.

Most of my friends, who for the most part have stuck to one academic path and have now begun their careers, often joke that I am going to be a “student for life.” And I know what they mean - that I am just going to continue doing Master’s degrees all my life – but I take that as a compliment: yes, I will be a student for life, just not a “University student for life.” Honestly, I loved university. And I felt like my blend of studies had given me what I was so desperately lacking after high-school: an understanding of how society works, doesn’t work and should work. On top of that, I had new stories to tell, and felt better equipped to tell them in the context of the world we live in. Why cinema mattered

Ironically perhaps, it was all these years of university studies that allowed me to understand the beauty and significance of cinema and rehabilitated my respect for filmmaking. I admired university professors because they had a regular 2-hour slot during which students were (mostly) intellectually invested in what they were talking about. They were in a position to share with an audience something that was important to them and therefore influence behavior and shape the world. If you think about it, 2 hours of listening to someone drop some knowledge on you is a long time – and multiply that by the number of classes, and you have some pretty strong brain-to-brain communication going on there. And then somewhere along the way, I’m not sure exactly how I came to see this, I realized that when people watch a film, not only are they intellectually invested, but they are also emotionally invested. And there is currently no other activity where people will commit all of their attention, both intellectual and emotional, for over 90 minutes to one other person’s mind, the writer/director. And therein laid the real power of the filmmaker. Filmmakers have a privileged access to people’s minds, to share a feeling, an idea, a message. Spielberg had touched more people and influenced society more than any one regular lawyer or judge or doctor or politician.

|

|

This, actually, should have been very clear to me from the start, for Spielberg is directly responsible for my own desire to make films. In the summer of 1993, my parents took me to a Cineplex in the north of England to see Jurassic Park. And I’m in no doubt: I can pinpoint this experience as the moment that sharply put into focus one of the many possible futures that were open to me at that stage. I had no idea what making a movie entailed but I knew that what I had just witnessed was awesome, that I wanted to experience it again and that I would learn how to replicate it for myself and for others. I sometimes wonder, though: what would my life be like if my parents that night had decided to see Life with Mickey or What’s Love Got to Do with It? (If you don't remember these movies, neither do I, and that's my point...).

Beyond my particular case, think for a moment of how films actually shape our common world. Suppose I asked you: What does an astronaut do? What’s his life like? What struggles does he go through, professionally and personally, back home and in the spaceship? Most of us don't hang out with astronauts very often, so we will have answers to these questions only through what we have seen in movies – 2001, A Space Odyssey, or Apollo 13, or Gravity, or Interstellar. Or what does it feel like to be criminal? Most of us will never know for real because we don’t want to go to jail, but we can all test it, we can all become gangsters for a couple hours from the comfort of our couch: just watch Goodfellas, or Once upon time in America, or The Godfather, or Scarface, or Snatch.

Cinema is not just entertainment or even a fleeting intellectual stimulant: it’s a space-time machine, a device to travel the multiverse and live other lives. A film is a short, safe and secure opportunity to live another life and wonder: what would I do in that situation? How would it feel to be that person or to live that experience? As such it’s a real-world shaping tool, because it expands our senses within it and broadens our individual experience of it. Just try to think what your life would be like and what your understanding of the world and of other people would be if you had never been exposed to a single film in your life (whether film of television). Sure, you would have books, but the same argument applies there too. Suppose there were no books or films. Just imagine how restricted our awareness of the world would be: anything outside our individual, immediate experience would exist only through tales spoken to us from others. This is why throughout human history, storytellers have always been around and important in any society: they expand the mind. Think for a moment of who we are: our expectations and behaviors with regards to making friends, dating, having sex, falling in love, falling out of love, getting married, being married, pursuing a career, having children, becoming old, being old, dealing with other people's death, dealing with our own death, etc. All these various aspects of life have been just as much, if not more so, shaped by movies and TV as they have been by any formal education or social conversation. We behave by mimicking others – our parents first, then those around us, and we construct our vision of the world with what is shown to us by those we can observe. And in this respect, film is probably the most diverse and complete source of models and information. Take a TV show like Friends, for instance. Given how popular it was when I was growing up and how cherished it still is by almost everyone I know, I’m certain this show played a big part in shaping our views on friendship and romantic pursuits and so, through its audience, in fact shaped society in its image. Imagine if Friends hadn’t existed (and that there was no other similar substitute), perhaps society would be a little different, perhaps we wouldn’t date the same way, or balance leisure and work in the same way, or enjoy coffee shops quite as much. People who want to become lawyers don’t wake up one morning and think that going to court every day would be fun; no, they mostly will have been inspired one day by some work of fiction depicting the experience of a lawyer or judge who overcomes adversity and restores justice, and enjoyed the feeling of being that character. They projected themselves into that story and in return that story shaped the real-life trajectory of an actual human being.

The flipside of all this is that writing a film is like creating a small life. You birth it and everything in it. And in a weird way I think this is one of the reasons why I enjoy writing: I get to create another life, one that, unlike the real world, I can control and determine in all aspects from beginning to end. This actually raises an interesting thought about character: sometimes, writers say that they have created characters that are so well defined that they take on a life of their own, making their own decisions. The writer is just there to report this imaginary world that is unfolding by itself, with characters who are acting as if of their own free will. But what makes such a character? If you’re writing a story with a strong character, let’s say a female protagonist, usually you will start by developing her backstory, where/when she was born, who her parents were, what her childhood was like, what she likes/dislikes, her character traits, is she shy, outspoken, smart, silly, adventurous, naughty, etc. Basically you are defining her determinants. What kind of person is she when we meet her at the beginning of the story? And this gives you some sense of the kind of decisions she will make as the story unfolds. Suppose then there comes a first turning point in the film where the protagonist faces a choice. As I said, some writers will say that their characters are so well drawn out that there can be no doubt as to what the character will chose: when her boyfriend asks her to fly away with him, she will say “Yes.” But as a writer, you still have control - you could very well override what you believe to be her natural answer and write that she says “No.” Then what? If saying “no” is so blatantly inconsistent with her character up to that point, then you might think the result is just that your character becomes inconsistent, and thereby unbelievable. But there are surely cases where two different, even opposite choices can be made, without either one seeming out of character. What are we to make of this protagonist now? How can we ever say that we are dealing with the same person to begin with? If facing a choice with high stakes, a person decides to lie rather than tell the truth, or to kill rather than let live, doesn’t that fundamentally change who this person is, and always was? Or does it create two new identities who happen to share a common past? One of the guiding principles of good storytelling is to reveal character through choices – the higher the stakes of the choice, the truer the character reveal, the stronger the reward for the audience. But are we revealing character through choice, or creating it? Or both? And what of our own choices? Every time we face a decision, is our relationship to that decision the same as the writer’s, who could literally do anything he wants, or as the character’s, who is going to do what his determinants tell him to do?

It’s probably a mix of both. When I look back at the origins of psi, there were many turning points that led me to want to make it. Why did I want to make films? Why was my mind never willing to let go of that ambition? Could I have really done anything else? Again, some things were out of my hands, and some were decision points where I could quite possibly have done two different and even opposite things. And this seems to hold true in the case of my project. If I look back and wonder what directly led me to begin it, beyond my original love for films, there are really two major factors, one based on a decision, and the other based on chance. Chance & decision

I’ll first explain the “chance” part. In September of 2012, I moved to Argentina with my girlfriend of the time, Ellen. We had both wanted to discover South America for a long time and so we spent the first few months backpacking through Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Chile and the Argentinian Patagonia. Eventually, in early 2012, we made our way to Buenos Aires where we hoped to settle down for a while. However, after our adventures, we had almost no money left. We had just enough to rent a room for 2 weeks and found ourselves with our backs to the wall: we each had to find a job otherwise we’d have to leave. The job market in Buenos Aires wasn’t great, especially for two people who didn’t speak Spanish well enough for any professional environment. The first week, we were sending resumes left and right with hardly any response. And then, at the last minute, a private middle school replied to Ellen offering her a position as an English teacher and I found the following listing on Craigslist: “In-House French/English Translator Wanted.” Just days before we would have had to leave, we both secured jobs and moved into a house in the Palermo neighborhood.

We stayed there for another 6 months. During this time, I had a 9-to-5 job at a translation company where I was responsible for translating, editing and proofreading documents in English and French. When eventually the time came to leave Argentina, I resigned from my job and they offered me a position as a freelance translator. Little did I know then, this freelancing job became the means to achieve everything that followed: I found myself with a job that paid relatively well and more importantly a job which I could perform wherever I wanted, whenever I wanted. All I needed was my laptop and an internet connection.

Had this translation company not put out that ad on Craigslist in Buenos Aires, I would never have become a freelance translator, and, upon returning to France, I would probably have ended up in a regular office job, with no time or money to make this film. This job really made it all possible. Throughout the production, I would be translating almost every day, at night, on planes, on trains, in hotel rooms, in coffee shops, making money whenever I had at least 20 minutes to kill – and often I’d look around at where I was, doing what I was doing, and think how lucky I was to have this job.

|

|

But this piece of luck is only half the story, as there was a clear element of willed decision-making that led to the coming-into-existence of this project. When we settled in Buenos Aires with our jobs, Ellen and I had been together for almost two years. We lived just blocks away from Plaza Serrano, which was connected to the street named after Jorge Luis Borges, the great author of The Garden of Forking Paths. Fittingly, our relationship was itself approaching a serious crossroads. We both knew we were eventually going to leave Argentina and would have to decide what to do then: would we walk hand in hand on the same path in the garden or take different paths at the fork? This question had always been central to our relationship: I was a French citizen whose base was in Paris, she was an American citizen whose base was in Seattle and we had met while studying at University in London. If you have ever seen Drake Doremus’ painfully accurate indie film Like Crazy, you’ll have a solid sense of what our life was like at times. As winter approached in the southern hemisphere, we were told that we would have to leave our house on the last day of June. The fork had arrived quicker than we had anticipated and this precipitated the decision. At that point, although we weren’t unhappy together, we both felt like there were good reasons to let it end. We both had some growing up to do before becoming adults who are able to commit to each-other for the long-run. For my part, my gut was telling me that I had not yet lived what I had to live before settling down with someone. I still had strong desires to return to university in France and I also knew that somewhere down the road I wanted to pursue my ambition to be a filmmaker. She probably imagined some version of her future where staying with me would inevitably distance her from her own personal goals too, and believed we would both be happier down the road if we sacrificed our relationship and individually formed ourselves fully first. The tricky thing, of course, for all, is being able to recognize when you are sufficiently formed to be in a position to hold onto the right person at the right time. In any case, this gave us a sense of purpose, a reason not to fight the separation and let it happen.

If torn decisions are the mark of our free will - as philosopher Robert Kane claims - the moments in life when we actually have a say in forming who we later become, then leaving Argentina was one of the most defining acts of self-formation of my life. Ultimately, following my instinct back to France, I enrolled in university to pursue the research I was interested in and ended up in the position where I decided to make this film. |

<------ Previous Chapter: Introduction

Next Chapter: The End: What It's About and Why ------>

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Next Chapter: The End: What It's About and Why ------>

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[email protected]

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.