Psi

Menu

VI - The Perfectionism Trap

Chapter 30

Narrator Attempt No. 2: Brit Marling

(May-Nov 2019)

Narrator Attempt No. 2: Brit Marling

(May-Nov 2019)

|

At the beginning of 2019, I moved out of my tiny chambre de bonne in the 9th arrondissement of Paris and moved in with Thom in a 2-bedroom apartment in the 18th. Time flew by, life went on.

With psi on hold, I wrote and directed another short film, called “Ukulele,” on a shoestring budget. Making “Ukulele” was a timely reminder of something I hadn’t felt in a long time: the rush of being in control of something you can actually achieve quickly, with your own means and on your own terms. Psi was supposed to be that and yet, by May 2019, the prospect of finishing it only filled me with dread. I kept banging on, of course, in the background with the pursuit of Diane Kruger and Juliette Binoche. In both cases, any time I’d hit up Isabelle and Peter, I’d get some version of the following update: “I sent the project but it’s not quite the right time, she’s sick, she’s on holiday right now, she's moving houses, she’s starting a new film, she’s not in the right headspace...” And yet whenever I asked them to be straight with me, both were confident, urging me to be patient.

But then something happened in May 2019. Several friends kept begging me to watch a new Netflix show called The OA. I didn’t know much about it, but when I saw that it starred Brit Marling – who co-created and starred in one of the films that initially inspired me to make psi, Another Earth – I gave it a shot. And, well... ...I was floored. I binged Parts 1 and 2 within a few days. And then it hit me:

Brit Marling. What about her? Why don’t I ask her to do the voice? How had I not thought of her before? How had I not thought of her first ? I had been so focused on the initial match between psi and Natalie Portman that I hadn’t actively explored anybody else. But I should have, because in many ways, Brit Marling made just as much, if not more sense. I had to reach out to her! At this point, I should pause for a second because you may be sensing a pattern here (I certainly am writing about this in hindsight): I get my hopes up about the highly unlikely prospect of reaching and convincing an A-list actress to be in my artsy, no-budget movie, then spend months trying to get her attention only to fail and try again. Did I not get it already? Did I not see that I was being far too stubborn and uncompromising in the pursuit of some unnecessary perfectionism? And the answer there is: yes, I did, but I didn’t care. I desperately needed the newfound sense of purpose and urgency, and with Brit Marling, I felt I had found the perfect fit. And as I psyched myself up for this new pursuit, I promised myself that this time, it would be the last attempt. There couldn’t possibly be anyone else better suited for the film, so if Brit Marling said no, I’d gladly go down a different path: I’d find a non-famous actress who I could actually speak to, and simply give up on the “famous-actress-playing-herself-in-another-life” element of the concept. Why her?

So, in June 2018, I adopted the same strategy as with Natalie Portman: I built a private webpage destined for Brit Marling, exposing all the reasons why I absolutely wanted her, and specifically her, to voice the character of the psychologist (remember, at this time, the "narrator" was meant to be the character's psychologist). And there were quite a few.

The first reason is that she very well could have gone down a more “serious/traditional/secure” path than acting, albeit not psychology. Like many people, she had an interest in acting from an early age, but her parents encouraged her to focus on academics, and she was a bright student. She graduated in economics at Georgetown University, where one summer, while interning as an investment analyst, Goldman Sachs offered her a job. But she felt a life spent there would lack meaning, and turned it down, opting instead to move to Cuba to shoot a documentary with an aspiring filmmaker she’d met at University: Mike Cahill. Right there, she had abruptly taken the reigns of her life and made a sharp turn. When she later moved to LA to pursue acting, she was frustrated at being offered the same, tired female roles. And so the only way to actually play original, challenging characters was to write them for herself. In 2011, she co-wrote, co-produced, and acted in “Another Earth,” directed by Cahill, and “Sound of My Voice,” directed by another young filmmaker she’d met at Georgetown, Zal Batmanglij. Both films were independently produced on a limited budget, and both went to Sundance, where all three of them emerged as exciting new talents. Marling had thereby imposed herself in the industry through sheer will and passion for storytelling and, more importantly, by going it her way. With her two friends, they’d made brilliant DIY films, with a true bravado and entrepreneurship, and this was extremely inspiring to many aspiring filmmakers, including me. Overall, I felt her early career and radical decisions resonated with the themes explored in psi about how chance encounters can activate life changes and how willpower can drive you to act on them in a self-determining way. But furthermore, looking at the stories she’d written, the characters she played and the themes her movies addressed, I felt there was a strong connection between her interests and mine: choices, regrets, determinism, free will, parallel lives. She often played characters who seemingly defeated the laws of physics (travelling through time in “Sound of My Voice”; being reincarnated in “I, Origins”; travelling to parallel worlds in “The OA”) to challenge the worldviews of other characters and pose fascinating philosophical questions.

Parallels with the OA

And The OA was truly the pinnacle of all this. As I watched the show, I couldn’t believe the sheer amount of similar paths we were treading: the concept of people travelling to parallel universe, the obsession with mapping out the various branches of the multiverse to find the “best one,” the philosophical and scientific implications of quantum mechanics, the concept of parallel dimensions as well as Everett’s “Many world’s theory,” the quest for self-identity and meaning in leading one life among many others. Netflix frustratingly cancelled the show after the second season, but even its brilliant, final cliffhanger promised new developments where Brit Marling would play herself in a parallel world where she’s married to her real-life co-star Jason Isaac, an actor who’s filming a TV show that is, presumably, an alternate version of The OA. It was perfect.

Even more strikingly perhaps, were the many narrative and visual parallels with psi. First of all, The OA makes several direct references to the "Garden of Forking Paths" by Jorge Luis Borges (it is mentioned in dialogue, and Season 1, Episode 6 is even called “Forking Paths”); psi begins with a quote from the same work. Admittedly, Borges is perhaps a little expected and hardly a subtle reference given the subject matter, but still, throughout The OA and psi, gardens and trees occupy a central narrative place. Marling’s character is even called Prairie, which I doubt is a coincidence. The OA Part 2 even captured in a more poetic way a central insight in psi, namely that the future is evolving in our minds, or from within our minds – in reference to the analogy between a 2-step kind of free will and Darwin’s theory of natural selection: thoughts are randomly sparked in our brain by quantum events, and are selected for by our character, desires and ambitions, thus determining our actions. As an illustration of this, I filmed a sculpture called “The Flowering of the English Baroque” located in central London, that shows a human head with flowers growing out of it. You can imagine how stunned I was when, in the final episode of The OA Part II (spoilers ahead), Prairie discovers that Hap is “cultivating” humans to literally grow the branches of the multiverse through their ears! Beyond greeneries, another common visual theme was mirrors. Again, this is perhaps a little on-the-nose given the subject of parallel universes, but nonetheless, the reference is constant throughout: in The OA, mirrors have an aesthetic and quasi-mystical power to peer into parallel worlds; while in psi, the whole film is structured as a reflection, and there are multiple uses of the mirror effect – a simple yet mesmerizing trick which is also used in some of The OA’s opening title cards.

But there was also another more random and uncanny visual parallel: the use of staircases. In The OA, stairs constitute a mysterious object of fascination as it becomes apparent they might connect places through dimensions, perhaps serving as passageways. This idea of different places being connected through spacetime is, again, a principle at play in psi with the juxtaposition of similar buildings and places throughout the 5 cities – with a particular focus on… staircases... and especially, spiral staircases.

All of these similarities just kept building up and fueling my desire to bring psi to Marling’s attention. When reviewing the “private webpage” I designed for her, listing all these points, I really felt there was something out of the ordinary here, some artistic resonance which, if she came to see it too, could quite possibly make her want to know more. It’s funny because the people around me, who I told about this new quest, were more extreme in their reaction and generally divided into two opposite camps:

Trying to officially get in touch with her...

So, the big question then was: how to reach her? I had 0 personal or professional connections to her or her entourage. At this point, I could just skip the next part and jump right to whether or not I succeeded. But the process is worth recounting, not because of any crazy ups and downs, but because of how this seemingly trivial act – offering a job to someone through official channels – became unbelievably Kafkaesque.

|

|

After some Googling and IMDB-mining, I found that Brit Marling is represented by CAA super-agent Hylda Quealy, whose client-list is a Who’s Who of Academy Award winners and nominees: Cate Blanchett, Kate Winslet, Marion Cotillard, Lupita Nyong'o, Jessica Chastain, Michelle Williams… Clearly, I knew Quealy wouldn’t just pick up the phone.

But that’s all I could do to begin with: so I called CAA’s headquarters in LA and simply asked to speak with Hylda Quealy. To which the receptionist politely replied: “Sure, let me put you through to her office.” Okay, easy-peasy. Seconds later, Quealy’s assistant answered the phone and, after I asserted with nervous gravitas that this was about hiring Brit Marling for a feature film project, she requested I send over the details for Hylda to review. At that point, I thought this would be the end of the road. But the next day, Quealy’s assistant transferred my request to Sara Leeb, the CAA agent in charge of voice-over work, who’d take things from there. So far, so good. On June 20, Leeb e-mailed to say she’d read the project and scheduled a meeting on July 8, when we spoke on the phone for almost 1 hour. She was surprisingly positive, impressed by the film’s ambition and pleased by the personal touch directed at Brit Marling. But before going any further, she got down to business: how much money could I offer? I was ready for this. I didn’t actually have much money, so I gambled and quoted a figure that I felt confident I could quickly pull together from various sources if Marling actually ended up agreeing. I won’t say here how much, but it was way less than what an A-list actress would normally be able to expect, and a bit more than a few thousand dollars – just about enough for Leeb to say: “Given the nature of the project, we can work with that.” I was glad to hear it. Agent, check.

But, just as I was about to hang up and enjoy this temporary victory, Leeb interrupted her own excitement by recalling that there was... one... condition... before she’d send anything to Marling: my film had to be approved by SAG-AFTRA - the largest actors’ union in Hollywood, of which Marling was a member - and psi ’s producer (whether that was me or someone else) needed to be a SAG Signatory (i.e. approved by SAG). This totally winded me. It was like reaching the final stretch of a marathon only to realize there’s a hidden detour up a steep hill. Because I instantly knew this SAG-AFTRA thing was potentially going to be fatal. Obviously, I assured Leeb I’d get it sorted and get back to her asap. But deep down though, I just wanted to scream.

It was one of those moments that made me think of how contingent the most annoying obstacles can be sometimes. A few minutes earlier, I’d never heard of SAG. I was finally making progress and cruising towards my destination – but no, here was this new pothole that came out of nowhere, like a sneaky, gratuitous act of God. I could so easily imagine a world where SAG doesn’t exist, or where SAG has nothing to do with me or my film. It’s like when you've been working on something important for hours and your laptop crashes. This didn’t need to happen.

Anyhow, I needed to deal with it. So, first things first: I had to get an actual, real producer who could submit the film to SAG and become a Signatory, in order then to be able to “hire” Brit Marling if she were to agree. A few months earlier, I’d met an up-and-coming French producer, Eve Brémond, the older sister of a high-school friend of mine, who’d seen psi and offered to help me out in the future. I went to her with my situation and she agreed to step in with her production company. With Eve’s support, we called SAG and asked for guidance in submitting the film. We first had to choose which kind of project this was: TV, Cable, Feature Film, Commercial, Music Video - we went with a section called New Media, as psi was more realistically destined either for the Internet or streaming platforms. But, as we first set eyes on the application file, we realized just how big a pitfall this was: we needed to fill in a Pre-Production Cast List, LLC Paperwork, Performer Contracts and Production Time Report Forms, Pension and Health Contribution Forms, etc. It was a nightmare.

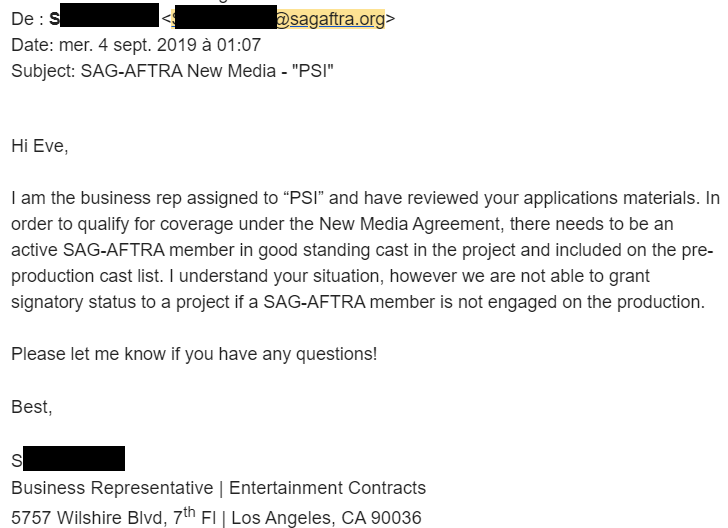

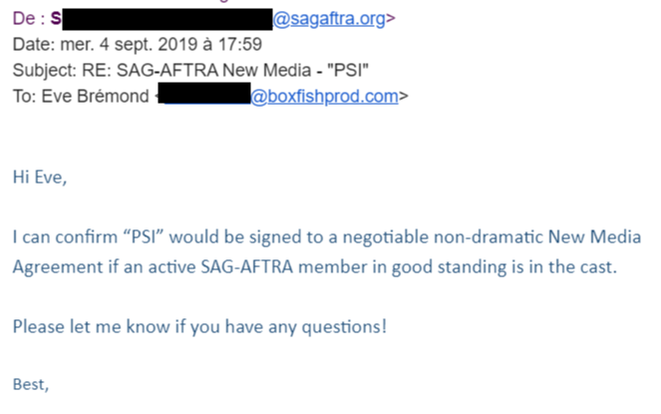

The whole thing was pretty ironic, too: I’d originally started this project to prove to myself it was possible to make a feature film outside the normal channels of production, and here I was now, retroactively needing to comply with the most bureaucratic requirements in the US film industry. As we crossed out entire sections of the application form, we realized that psi literally fulfilled none of SAG’s criteria. First of all, you’re supposed to file your submission before even shooting. Second, all the people involved in the production must be paid union wages, with all the required benefits, insurances and legal working hours. None of which was the case on my project. And finally – and this is where the whole thing just got stupid - in order to submit the application, we needed to provide Brit Marling’s SAG-AFTRA Registration number, which obviously we didn’t have. SAG informed me that it should come from the actress herself or from her agent. So, I called Sara Leeb at CAA but she claimed SAG should be the ones to provide it. I went back to SAG who again refused and were adamant that this registration number – which was essential to the application form – should come from CAA. This chicken-and-the-egg deadlock drove me crazy - and no amount of explaining to both sides that the whole point of this was to hire their talent made them budge. It was insane. Eventually, out of annoyance more than anything, we filed the SAG application without Marling’s registration number, attaching a letter that explained why and asking for leniency with regards to all the other criteria. On September 4 - almost 2 months after starting this whole affair - we got a reply from a SAG business rep. And while she completely sidestepped the preceding issues as though they were never really a big deal, she threw another left-field wrench into the wheels: "We are not able to grant signatory status if a SAG-AFTRA member is not engaged on the production." As I read this, I was yelling at my screen: “The whole point of this is to engage her!”

I hammered out my reply with a final attempt to strike some common-sense agreement: “Marling’s agent wants assurances that the project will qualify for SAG before approaching her. So, to move forward, can you confirm to me that, if Brit Marling were to agree to the part, you would then grant Signatory status to the project?” SEND! I was really itching for them to reply something like “Sorry but actually, to qualify, the film has to be shot 75% in the United-States…” But that evening, SAG finally gave me what I needed: See, wasn’t so hard!

Union, check.

Finally, I could go back to Sara Leeb at CAA with the green-light. On Monday, September 9, we spoke on the phone again, and this time, she confirmed she would now proceed to sending the project to Brit Marling. At that point, honestly, I felt positive. This time, her actual agent (well, her voice-over agent, but still) said she’d send the project to her. I had to believe that Marling would see it now, sooner or later. I could sit back and enjoy the anticipation.

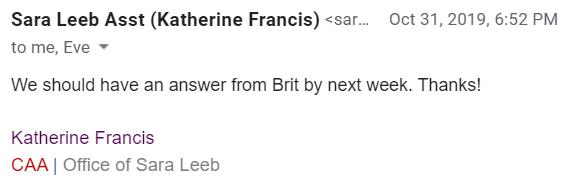

A few weeks later, towards the end of September, Leeb reported she hadn’t heard back yet and asked me for a deadline. This was a tricky question. I didn’t want to mess up my chances with too-early a date, but I also didn’t want to come off as being too nice or indecisive, so I said November 30, adding that obviously, I was flexible. If Marling was interested but not available before another few months, I could wait (I’d spent the better part of the last 18 months trying to get this right, so…). Over the next few weeks, I checked the stats on the private webpage I’d built for Brit Marling to see if it had any activity. But it didn’t. It included a password-protected screener of the film on Vimeo, but the number of plays (not views, just plays) remained stuck on 2 (by me and Eve), and its geographical stats showed it hadn’t been clicked anywhere outside of Paris. Eventually, after seeking another update on October 31st, Leeb's assistant finally gave me some exciting news: The pressure went up a notch. I now had a timeframe. By November 7, I should have an answer. Although I resisted the temptation, I really wanted to tell my more cynical friends, the self-described “realists” who doubted my ability to ever get in touch with her, that I was almost there. I wanted to prove them wrong, to show them that if they felt uncomfortable with my self-belief, it was because of their own inhibitions. I could get in touch with her, and I could potentially convince her to be in the film.

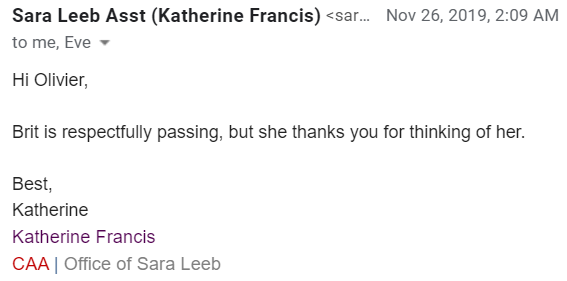

The week went by - November 7, no news. Then 10 days, then 15. I asked for an update – still nothing. The stats hadn’t changed on Marling’s webpage. I asked Amélie, my agent friend in Paris, how she felt about the whole thing, and she literally said: “Call the agent again. Call her 5 times a day. You have to harass agents to get anywhere.” I hated that. I already felt like I was pushing it. But eventually, on November 25, my patience broke and I e-mailed Leeb again, hoping this would make a difference. And it did, because the following day, her assistant replied: I asked if Marling had said anything else, any feedback as to why she declined:

This took a few moments to sink in.

Actress, uncheck.

The naysayers had won. I felt rejected, foolish and naïve. What was I thinking, with my little webpage and my meticulously crafted plans. The Vimeo link didn't show any more views, and sure enough, the delusional doubts crawled in again: Did she actually even see the project? What if she had assistants who screen her e-mails and missed it? And if she did get it, what did she really think of it? Why didn’t she ---

I had to shut myself up. Marling didn’t want to do it, and I had to respect that. End of story. |

<----------- Previous Chapter: Narrator Attempt No. 1: Natalie Portman

Next Chapter: Narrator Attempt No. 3: Myriam Ajar ----------->

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Next Chapter: Narrator Attempt No. 3: Myriam Ajar ----------->

TABLE OF CONTENTS