Psi

Menu

III - THE INTERVIEWS

Chapter 16

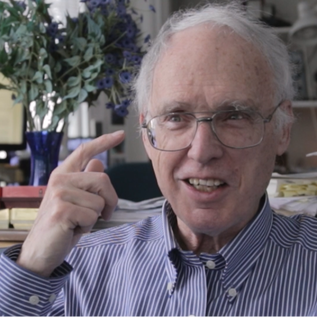

Bob Doyle: The Information Philosopher (Feb 2015)

Bob Doyle: The Information Philosopher (Feb 2015)

|

My last stop on this cross-USA trip was Boston, where the cluster of great universities meant a concentration of experts in many different fields. I had arranged three meetings there: first with Bob Doyle, then with Daniel Dennett and finally with Max Tegmark. The first on the agenda was Bob Doyle, who is in some respects the “outsider” of my cast of experts, as he is the only one who wasn't currently part of academia. It is hard to sum-up what he does in one line and a quick look at his CV reveals what an diverse life he has led:

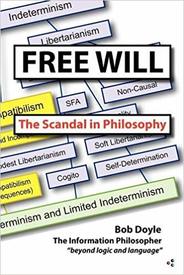

Doyle is a bit like a philosophical engineer: he sees things like problems to be solved and free will is no exception. Combining his knowledge of both quantum physics and philosophy, he has built up his own model to account for free will, which he calls the “Cogito model” of free will.

Before explaining how it works, it is necessary to understand a fundamental concept in his line of thought, which is possibly the most convincing way I've so far heard of making sense of both the apparent randomness of quantum physics and the apparent determinism of the every-day world. This concept is “adequate determinism,” sometimes called “statistical determinism,” and the idea goes like this: quantum physics applying to all particles, there is no strict determinism at any level or scale in the physical universe. Therefore, what we routinely call “determinism” is in fact nothing more than a theoretical framework that applies to our scale of experience and allows us to use accurate mathematical models to predict things, such as the movements of planets or billiard balls. This is possible because for objects of a certain size, there are so many individual particles involved that the random probabilities of each and every one of them become “averaged over” to the point of near statistical certainty (law of large numbers). In other words, what we see as being determinism in the human-scale world (Newtonian physics), while almost always reliable for all practical intents and purposes (like sending men to the Moon), is actually only an “adequate determinism” of many, many, many quantum events that, averaged out, approach the near statistical certainty of classical physics for big-enough objects (an atom, for instance, would already be big enough). This concept of “adequate determinism” therefore could serve as a theoretical framework to bridge the apparent contradiction between indeterminism and determinism, and thus pave the way for a rebuttal to the “Standard Argument” against free will that doesn’t need to reject outright one or the other, but can cleverly accommodate and combine both. |

|

With this in mind, Doyle’s “Cogito model” of free will explains it in two steps, in line with many other “two-staged models” from William James all the way to Martin Heisenberg (son of Werner Heisenberg). He argues that free will is best understood not as something that expresses itself in a single moment (the decision) but over a temporal sequence in the brain leading up to a decision.

In the days following our interview, Bob and I spent a few other afternoons discussing his other endeavors, both in philosophy and entrepreneurship (he owns a studio which is like a mad inventor’s cave, with computers, gadgets and video games everywhere) and I am glad to say that we have become rather good friends. Having a lifelong desire to help DIY film projects to get off the ground, and knowing that I was heading into the editing process on a tight budget, Doyle extended his own Adobe membership to me, and gave me an extra monitor and external hard drive. So in addition to all the other roles he's had throughout his life, Bob's also a bit of a patron!

|