Psi

Menu

III - THE INTERVIEWS

Chapter 11

The Issue: Freedom in The Modern World

The Issue: Freedom in The Modern World

|

I began this project with a fairly simple but broad question: are we free to lead the life we lead? Developing this question led me to approach it from two different angles: a social one (i.e. are we free in terms of choosing our life path? why do we struggle to do so and to be happy with it? etc.) and a more fundamental one (i.e. the question of free will and determinism). But my interest and engagement with these two levels of questioning was at first only personal, in reaction to my own experience and those of my friends around me. I had noticed that most of them all shared the same concerns I did, and that these doubts were fairly preoccupying to almost everyone I knew: What should they do with their life? Had they chosen the right path? Will they ever start enjoying their work? Should they commit to their girlfriend/boyfriend? Will they ever stop regretting some decision they made? And so on. All of these existential questions were consuming and evidently at the top of my generation’s list of daily worries. This was particularly intriguing to me because at the same time we have been told our whole lives that we are lucky to be as free as we are and that we should make the most of it.

Choosing a life

It's no wonder, then, that 3 of my closest friends recognized themselves in the film and played an integral part in making it. I’ll quickly give you the examples of their actual lives, because despite the big differences in their respective chosen paths, the similarities in terms of life doubts are striking. I'm currently writing this in 2019.

Example 1: Paul

Paul Marinucci (he’s the guy in Helsinki), he’s now 32: in high-school, his sole interest in life was music. His father was a boat engineer and his mother a chemist, but he was a classically trained pianist, he was a founding member of a band called Miss Take (with our other friend Thom, who I’ll talk about in a moment) and he idolized French multi-instrumentalist and Amélie-famed Yann Tiersen. He dreamed of becoming a professional pianist and writing music for movies. So, when graduating from high-school, Paul enrolled in med school and studied chemistry. He then went to get a Master’s degree from a top business school in Paris then started working in the pharmaceutical industry. Over the years, every time I saw him, the main subject we talked about was: music. Throughout college, he still produced his own tracks, printed his own CD’s and sold them to friends and relatives. And even though he was learning about experimental chemotherapy treatments, his real dream was: being the next Yann Tiersen. I’ve heard him a good 50 times say: “I swear, after I finish this year, I think I’m just gonna quit, build my own recording studio and seriously focus on composing music.” Paul today works as a product manager for a major pharmaceutical company, he’s happily married, has just bought an apartment in Paris with his wife Julie (who’s also in the film) and they have a baby girl together. Verdict: he’s very happy, although he doesn't spend much time playing music at the moment.

Example 2: Marie

Marie Lefèvre (the blonde girl who’s with me in Jerusalem), she’s now 33. We met when we were 22 in University. She had already started working in the NGO/humanitarian scene, first in Paris and then on short missions abroad in South America and the Middle East. Every time she returned to Paris after a fix-term contract, she became a ball of nerves: “What do I do next? What kind of work should I do? NGO, governmental, private sector? Where? Middle East or should I branch out to other continents? But… my life is in Paris!” On the one hand, she had built-up a lot of experience in the Middle East and established a good professional network, but on the other, she missed being in Paris, close to her friends, family and culture. So what to do: career or relationships? After leaving Jerusalem, Marie got a job in Tunisia and promised herself: “That’s it, this is the last one, after Tunis, I’m moving back to Paris.” Marie is now married to Remi, a Jordanian she met in Tunis, mother to their first son and living in Amman. Verdict: she’s very happy, but they still talk about moving to Paris someday.

Example 3: Thom

Thom Lefèvre, who was in high-school with me and Paul, always loved music and theater as a teenager. Aside from being the drummer in Miss Take alongside Paul, he was a regular cast member in the high-school plays. But he didn't know what he should do afterwards. What to study? Where? Nantes? Paris? London? As a backup, he started with a 2-year business course in a local school, before moving to London to study music marketing. For several years, he managed bands and worked in pubs. When I met up with him to shoot the scenes for psi, he was 28 and told me he felt that his passion for acting was calling and he had to make a move in that direction before it was too late. A few months later, he quit London and moved to Paris to start fresh. He enrolled in acting classes, in 2017 he was the lead in a play in central Paris, and is currently an actor, making his way in the French industry. Verdict: he’s very happy, pursuing his dream, but troubled by its uncertainty.

Counter-example: my parents

These stories may seem rather common in Western societies, and that's because, to most people living in affluent countries, they are - but on the scale of human history, they aren't. They are rather exceptional. These types of questions and doubts have become prevalent because of (thanks to) affluence and options, and these good things come with new challenges – a lot of options, a lot of expectations, a lot of hesitation, mental torture, back-and-forth, stunted hopes and leaps of faith. I don’t remember hearing the same stories from my parents when they told me about their youth. They had issues, don’t get me wrong, but of a totally different kind and, in many ways, tougher.

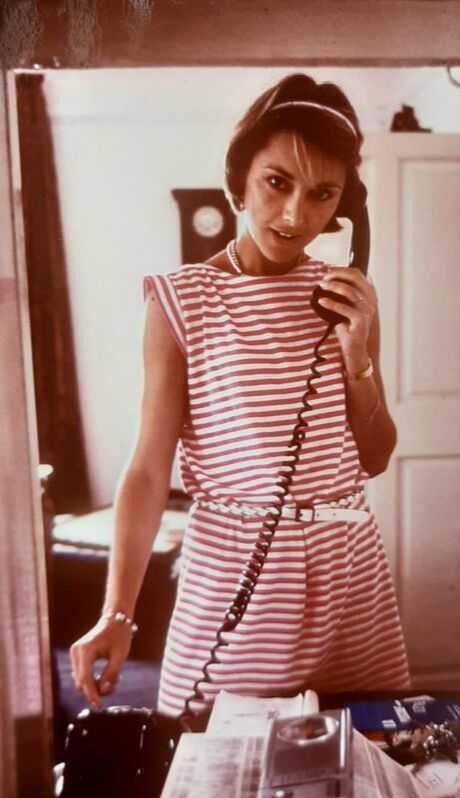

With both my parents, there wasn’t originally much hesitating, or dilly-dallying, or existential crisis about what they were doing with their life. Things just seemed to happen and they were pretty happy with it. So as I brewed my film project, there definitely seemed to be something unique about the situation the newer generations found themselves in, and this was the first side of the freedom-coin I wanted to get more expert insights on for the film.

Free-will and determinism

The second side of the freedom-coin appeared originally as an outgrowth of the first, when I started studying philosophy at university. As my ethics teachers would question us on what makes us “us,” I was quickly drawn into the so-called free will debate: are we free to lead the lives we lead, or are there other factors at work that make our freedom merely an illusion? Perhaps, after all, the existential questions I was grappling with were in many ways moot, if at the end of the day everything is just part of the plan for the Universe? Perhaps my Dad could never actually have become anything else than a photographer, and my mom anything else than an airline hostess. Perhaps they were destined to meet and I was destined to be born as I was.

Making my way through the free will landscape, I was particularly drawn down two particular rabbit holes which I find to be the most exciting frontiers of human inquiry today: physics (both quantum and astro) and neuroscience. On the one hand, an outward exploration into the infinitely tiny and infinitely immense, the infinitely close and infinitely far, in a bid to understand the origins, nature and functioning of objective reality. On the other, an inward exploration into our brain and minds to better understand the origins, nature and functioning of our subjective reality. Both promise earth-shattering and mind-blowing insights into everything that matters, the bedrock for all knowledge. With these two disciplines being so vast, naturally my interests funneled into several more particular subjects pertaining to human freedom: What does science tell us about the causal order of the world? To what degree do we control our lives and decide who we are and wish to become? Are we free in the truest sense (i.e. is there something special about us that makes us the originators of our own wills, the causes of our own ends) or are we entirely the product of factors over which we have no control? Does quantum physics change our place in reality? And what about these parallel universes we often hear about? Do they exist and what do they entail? These questions were each so broad and complex that to properly explore them, I felt it necessary to talk with experts, not only for my own understanding, but for offering the audience the most trust-worthy source of information. Furthermore, all these questions on both sides of the freedom-coin are intertwined and play into each other to various degrees and, like almost everything in life, are all part of an overarching, directing quest: how to achieve greater well-being and happiness? We want to understand how the world and our minds really are and function in order to make sense of them and draw some conclusions for our individual and collective well-being. So, while John Stuart Mill would argue that you don’t derive an ought from and is, we still want to know what is in order to decide what we ought to do. And for this purpose, I thought that conducting interviews with experts would be important – because before being philosophers, astrophysicists, neuroscientists, psychologists or economists, they are first and foremost people. People who have life experience worth learning from. I’ll here present the interviewees one by one, how I came to meet them and some thoughts on how our conversation related to this project. |

[email protected]

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.