Psi

Menu

IV - POST-PRODUCTION

(March 2016 - Sept 2017)

(March 2016 - Sept 2017)

Chapter 22

Editing: The Puzzle From Hell

Editing: The Puzzle From Hell

|

Over the course of the first couple years of the project when I was shooting, I had been in touch with a few editors who had shown interest in taking care of the post-production. But as the editing phase approached, I realized that I would do the editing myself. It was just the nature of the film that made it difficult for me to hand over my rushes to an outside editor. Most of the film was shot on the fly, with the assumption that I would build the film in the editing room. My film had no screenplay, no precise shot-list, no storyboard. I had hours and hours of disjointed rushes (not to mention the 13 hours of interviews) that if I handed everything over to 10 different editors, they would make 10 completely different films.

Editors are often considered the “third writer” of a film anyways, but the degree to which this is actually consequential really depends on how the film was written and shot. Typically, feature films still constrain the editors with the screenplay and the footage. The editor can only deviate so much from the material handed to him from those who came before. Here, these constraints were virtually non-existent. The film was entirely in my head and was going to be made in the cutting room. If I got an editor, I would essentially have to sit through the whole process with him and walk him through what I wanted. It was just not efficient. Plus I couldn’t expect from anyone else the type of commitment required to edit this film, given the lack of pay. So, much like the decision to act in the film, the decision to edit was one I took initially out of necessity.

To paraphrase Douglas Adams, editing is easy, you just have to stare at your footage until your forehead bleeds. The reason it was so difficult was precisely because I didn’t have a clear blueprint on which to lay the material. My first step was to un-rush all my footage from the different locations, list what sequences I had in each city, then deconstruct the interviews, categorize them by theme and select the best bits. I jumped right into the edit on Adobe Premier Pro and wasted about 4 months thinking I could piece the film together right there. But because I had shot a lot of footage with only a general idea of what the final film would be like, I had set my own trap to fall into: there we so many things I wanted to show and say in the final film, it became this huge problem I needed to solve. Imagine trying to build a puzzle where you are cutting out the pieces yourself while designing the final picture.

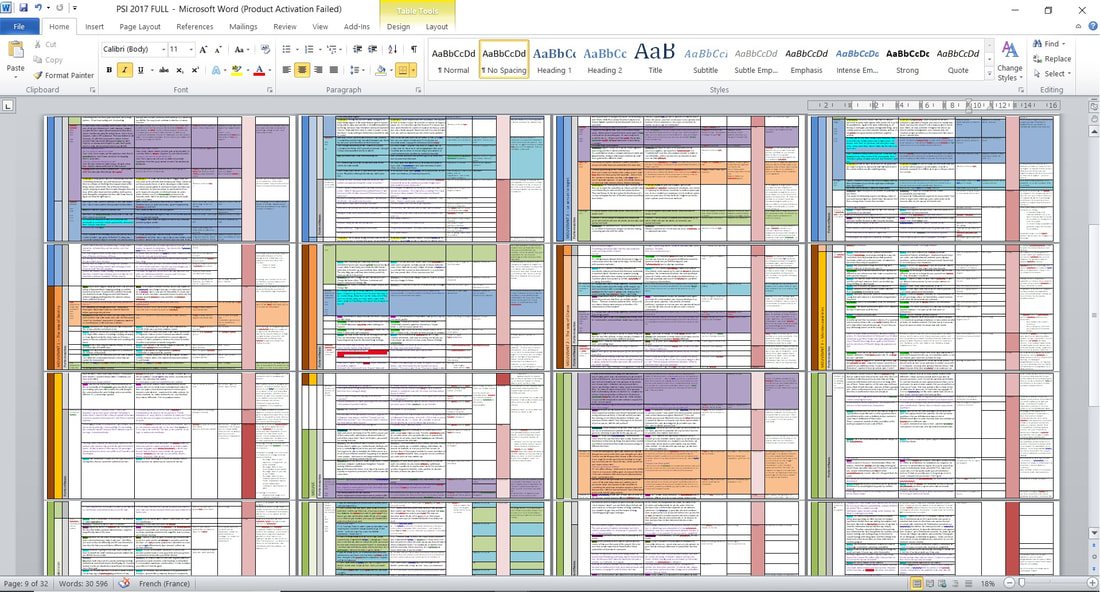

So eventually, I adopted a different strategy: I transcribed all the clips (from the fictional lives and from the interviews) into a gigantic spreadsheet and started editing in Word without even opening Premiere. This made it somewhat easier – or at least less time consuming - but still, I felt like I was trying to solve this massive Rubik’s cube: from time to time, one face would start looking pretty good, but then as I’d go to solve the next face, I’d mess the whole thing up again. |

|

For several months, the editing process got me pretty depressed. Every morning I’d wake up with this terrible sense of dread that would make me just want to keep sleeping. After my first coffee, I had about 1 hour of good vibes, after which the cogs in the enigma would stiffen and grind me to a halt. So I procrastinated, cleaned my room, tried going to the gym… but nothing worked. I binge-watched TV shows. At one point, I was stuck on the same page for almost 2 weeks.

|

|

The problem I faced at his stage of the editing process was, fittingly, a question of choice: Which way to edit? Which combination of shots will yield the best movie? Should I just “go with one version” and be happy with it? Or should I continue testing different combinations? When do I reach the point where “enough is enough,” accepting the fact I’m giving up on potentially better versions?

There are infinite ways to edit shots together and so many things you can tweak that will change the effect: the order of the shots, the length of the shots (sometimes just half a second more or less conveys a different feel and meaning), the music (what kind of music? should I edit to the beat or slightly off?). Given all the shots I had and all the music I could potentially use, I was constantly teased by the thought that there was one absolute best edit to make and that, if I wanted to find it, I had to keep doing tests and look for it. The trouble with this line of thinking is that finding it would require years of testing every possible combination, perfecting through trial and error, and having a system that allows you to not only remember how you evaluated every previous version but then to compare versions in some objective way. But then it dawned on me: Can you even ever find a “best” edit, no matter how long you search for it? What is the “best possible” anyway? What does this even mean? “Best” is an evaluation, so it can only exist and mean anything within an evaluator. So what this question really implies is this: the best to whom? Suppose I begin writing a film and at the end of the first act, the story can go in two directions; suppose I write both and then at the end of the second acts, each story line then branches out into another 2 stories, so that by the time we reach the end of the third act, my movie has 4 different stories and endings. That’s four possible movies to make. Which one is “the best”? Supposing all four have their strengths and weaknesses, what will determine “the best” is not entirely inherent to the story. There are of course some objective measures of good storytelling, but it’s conceivable to have more or less 4 equally well written stories. So what ultimately makes one of them the best rests in the appreciation of each individual viewer. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, as they say. And different people will have different preferences. Who then decides which is best in an absolute way? Do we take a vote? Barring alternate endings on DVDs and interactive "chose-your-own-adventure" content, movies have one storyline, one beginning and one end. We enjoy it or we don’t (oftentimes, we think up alternative endings which we claim would have made the film better) – and as an author, you have to make that determination based on what is closest to what you’re trying to say, and stick with it. And that’s, ultimately, what makes it the best. The real answer to the question “The best to whom?” is: the best to me, the filmmaker. Perhaps I had to focus my energy not on achieving some objective best - as defined by popularity or critics - but on expressing as accurately as possible my subjective intent and let that movie live among the many million different versions it could take. If this one version was the one I wanted, then I could legitimately stick by it, ignoring all other options. My purpose would dictate my course. This, obviously, is something that applies to life in general. Given that there is no “alternative ending” to life, what determines “the best” is not the choice, the but the experience. Perhaps the key to a “good life” then is to be a “good audience.” This points back to Schwartz’s imperative to have modest expectations in order to enjoy the result. Which films are usually the most disappointing? It’s those that were hyped-up beforehand by critics and friends. But what happens when you stumble across a film you knew nothing about, or you see a film that you were told was just ok but turned out to be pretty good? These are the films you enjoy and remember. Furthermore, it’s not just a question of having modest expectations: it’s a question of finding values by which to lead your life. Just as the writer/director/editor is asking “what am I trying to say” as a way of focusing his work, people who have purpose can subject their choices to this purpose – thus confidently excluding what is not in line with it. Purpose is what gives you confidence to pursue one path at the expense of all others, and is the good reason keeping regret at bay.

So returning to the editing process, the only way to get ahead is to have a plan: what am I trying to achieve, what feel do I want to convey, what message am I trying to communicate? Once I have that settled, I can then use the pieces at my disposal as a means to an end. If you don’t have these finalities, the telos, you are aimlessly trying combinations, progressing in murky waters and constantly looking back and sideways for fear of getting lost, instead of ahead at where you want to be going.

So, as I faced my massive Word spreadsheet, I focused my energy into answering the following question: what is this film about? I had to define the controlling idea and structure the film around it. This would bring into focus the important bits and allow me to confidently exclude all surplus. The answer was pretty clear: it’s about freedom. Ok. But then how to tell it? My main problem at this stage was the sheer amount of content I had. I didn’t know how to get it all into one film. A breakthrough came when I established what became the broader structure of the psi project. Originally, my project was only a film (which was itself at first supposed to be a short film) and that grew in size with the interviews. But as I was struggling to choose which parts to keep, I soon realized that I could exploit the rest of the interviews as an accompaniment to the feature film, to inform it and provide extra food for thought. And this is how, in addition to the current journal, the third piece of the project came to be: a series focused on the interviews, which I later came to call the Talks. This really liberated me because I was then far less reluctant to cut pieces of the interviews from the feature, knowing they would find their place in the series. Together with this journal, they would form a triptych. Having made this adjustment to the project's overall design, I could then move on more purposefully with the film and focus on its structure. I had all these different elements to combine and in order to bring them all together, I needed a backbone. This structure would allow me to keep track of the visual themes, the editing pace, the narrative balance and, as I would come to see, it would be extremely useful for composing the music. |

|

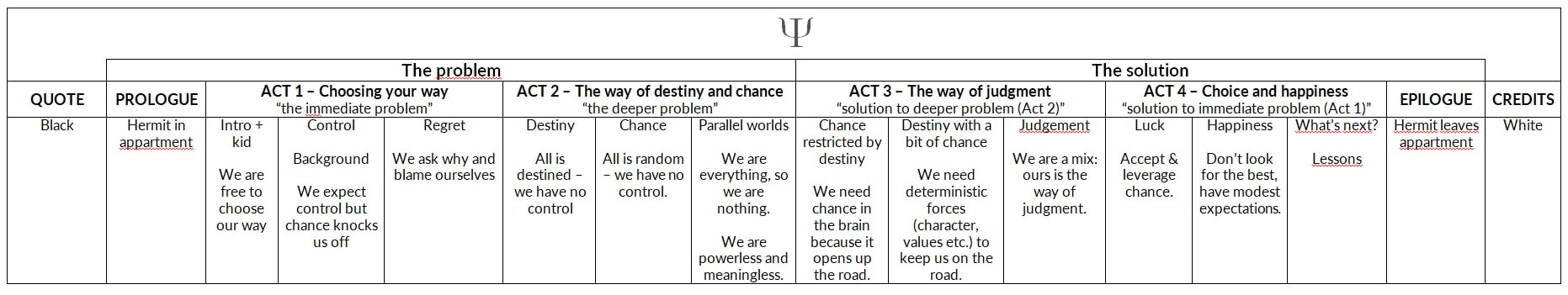

Over several months, the film found its structure: 4 acts, each act has 3 movements, and each movement is in 2 parts (a “presentation” part, which shows the fictional lives, and a “contemplation” part, which is where the narrator reflects on what's happening), with the whole thing book-ended by a prologue and an epilogue. Furthermore, the whole film is structured in a mirror-like fashion, with parts either side of the center in reflection of each-other: Act 2 and Act 3; Act 1 and Act 4; the Epilogue and the Prologue, the opening and closing shots; and finally the opening quote and credits. Remember, all this structural work was being done in Word and it took roughly 6 months to get the full skeleton in place. But once I had it, adding the meat to the bones went much quicker: I just filled in the spreadsheet with the footage at my disposal and within a few weeks, I returned to Premiere Pro to assemble the puzzle. And putting the film together with purpose was actually a very rewarding experience: I could finally see my film being born.

Editing the series of Talks

In parallel, I laid the groundwork for editing the interview series. This was unbelievably time-consuming as I had to break down 13 hours of interviews with 9 experts into digestible episodes of no more than 30 minutes. Furthermore, I wanted the overall series to have some coherence, where each episode has a singular theme and together they pursued an overarching quest.

I can't really say how long it actually took me to edit the series as I kept working on it for several years. But what saved me was approaching it like I did the film: I transcribed all the interviews and edited the episodes in Word. What was really hard was choosing the right insights, avoiding repetitions and ordering them in such a way to give the impression that these 9 experts were all working together, almost responding to each other. One interesting aspect of this process was noticing leitmotifs that emerged across these conversations. In fact, the final episode of the series, on "Happiness," is structured around three such common themes that appeared almost consistently in the personal experiences they shared: the role of chance and randomness in their life, their ability to be "satsficers" (7 of them claimed to have no regrets in life), and the importance of their personal relationships (especially with their wives). But there's another leitmotif that isn't as obvious as it pops up throughout the series, but it's one that I find telling because it has to do with the theme of film and storytelling, and cuts through all the different issues explored in psi, whether free will, physics, choice and regret. First of all, Doyle explained determinism as though, at the beginning of time, what started it all was like "a screenwriter, director and producer of a film" who "set the machine in motion" and "we're just watching the movie." Tegmark similarly explained Einstein's view of the universe by claiming that "if life is movie, space-time is the entire DVD." While Gazzaniga granted that research in neuroscience was showing that "we really were just in this movie that was being calculated elsewhere and we're just experiencing it." Gazzaniga went on to explain that, within this movie, our sense of agency is constructed by the "interpreter module" in the brain, which is constantly "making up a story" to explain life, which echoed perfectly with Strawson's account of "narrativity," the theory in psychology that "to be narrative is to experience your life as a story of some sort". Strawson himself admitted to being non-narrative, offering a personal memory that now seems to him more like a film than a first-person experience: "I'm not there. I'm just the camera." This sounded perfectly like what Gazzzaniga hypothesized about a person who didn't have the interpreter module, describing them as only having "snapshot" memories "with no weaving of a story." This narrative component in turn resonates with Giorgio Coricelli's research on regret, as he drew heavily on "counterfactuals" and the "fictive component in the brain." Which evokes Dennett's claim that consciousness, just like free will, is just a "bag of tricks" - like movies - and when confronted with the claim that determinism made us puppets of causality, his reply was: "What if you were a puppet that was controlled by itself?" Again, this idea of a show being put on. Kane, for who libertarian free will isn't an illusion, grants that if it was, we could be "fooled into it like in the Matrix". But for him, libertarian free will puts us both inside and outside the film, as "we are authors and characters in our own stories all at once." For whatever reason, this theme of movies, storytelling, and illusions was constant throughout the conversations, and I think it says something about how fiction and real life are deeply intertwined in our thinking, almost like two flipsides of our perception of reality. |

[email protected]

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.