Psi

Menu

IV - POST-PRODUCTION

(March 2016 - Sept 2017)

(March 2016 - Sept 2017)

Chapter 23

Music: The Key of Collaboration

Music: The Key of Collaboration

|

Early in the process, I had asked my friend Paul (who's in the Helsinki life), a trained pianist, to compose music for the film. Throughout most of 2015 and early 2016, he regularly sent me short pieces, testing different styles and melodies. I would give him feedback on which ones I preferred and how I would like him to develop them. However, as the project kept growing in scope and ambition, it became clear to me that listening to piano for 90 minutes was going to be problematic. So we would need to orchestrate the music – and for that, we needed some help.

Around April 2015, I spent a couple months inquiring left and right for musicians, but unfortunately those I got in touch with through friends were either busy or declined due to lack of funds. Turning to the Internet, there were so many potential composers out there that I just didn’t know where to start. Also, I didn’t really know how to approach them. Not only did I face the “payment” hurdle, but artistically what I was offering was a little tricky: I still wanted Paul to be involved and so it was probably a little weird contacting composers asking them to work partly with someone else’s material. Additionally, if I did convince someone to help with the music, I didn’t want to wait a few weeks for them to send me some tracks and feel pressured into liking them out of reluctance to extend a collaboration that might be costing me money.

For a time, I considered licensing tracks that had already been composed. I found several very nice websites, such as The Music Bed, The Music Case, Marmoset Music and Premium Beats, that all offered some pretty obvious advantages: the production quality was good, I could download the tracks I liked and edit to them before even buying them and the price was relatively affordable. For online use and festivals, tracks cost about 200$ each – I had estimated I may need between 10 and 20 tracks to cover the film, which meant a budget of $2000 to $4000. However if the film was shown publicly anywhere else, or if it got any kind of distribution, then the licensing agreement had to be changed for all the tracks. And this just seemed to me like one giant legal and financial nightmare, as their status would keep changing and the costs would keep getting exponentially bigger. Besides, licensing tracks bugged me for another reason: the music would not have been composed for the film, and so it would have no particular identity. And so finally, around March 2016, I got round to exploring the option I had postponed thus far: finding a composer who would be interested in the project and willing to work on a tight budget. And amazingly, the first page I looked at was the last. I found an article that introduced 5 young French composers who had recently won their first awards. I went to their websites, listened to their music and identified one whose musical style matched what I was looking for: Alexis Maingaud, 28 at the time. I sent him an e-mail, and his interest was spiked by the film's subject matter and scope. We met the following week in Paris and clicked right away: when he asked me what musical influences I had in mind, I could see his eyes light up as I mentioned Max Richter, Phillip Glass, Abel Korzienowski, Ludovico Einaudi and Johnny Greenwood. Despite the "DIY" nature of the project, he saw both an artistic opportunity and a professional challenge, and for my part, I was speaking to a composer who clearly understood what I wanted.

After our first couple of meetings, I noticed however that we had set off with a slight misunderstanding about the budget which turned out to be a useful test of the robustness of this project’s motivations. I had told him that I planned on showing my film to several production companies, including Mandarin films (who I had worked with by that time), and Alexis thought they were going to finance the music. He sent me an e-mail saying that with 70.000 euros we could probably do a great job. At that point I told him this wasn’t going to happen, not so much because I couldn’t go around and ask for money (which may or may not have been successful), but because it wasn’t the plan, it wasn’t the nature of this project. If I did go out and ask for money, and if I did manage to convince a production company to invest, then we might as well start the whole shoot over, with better equipment and a crew. But then it would no longer be what I wanted it to be: a film that most people could do with their own normal savings.

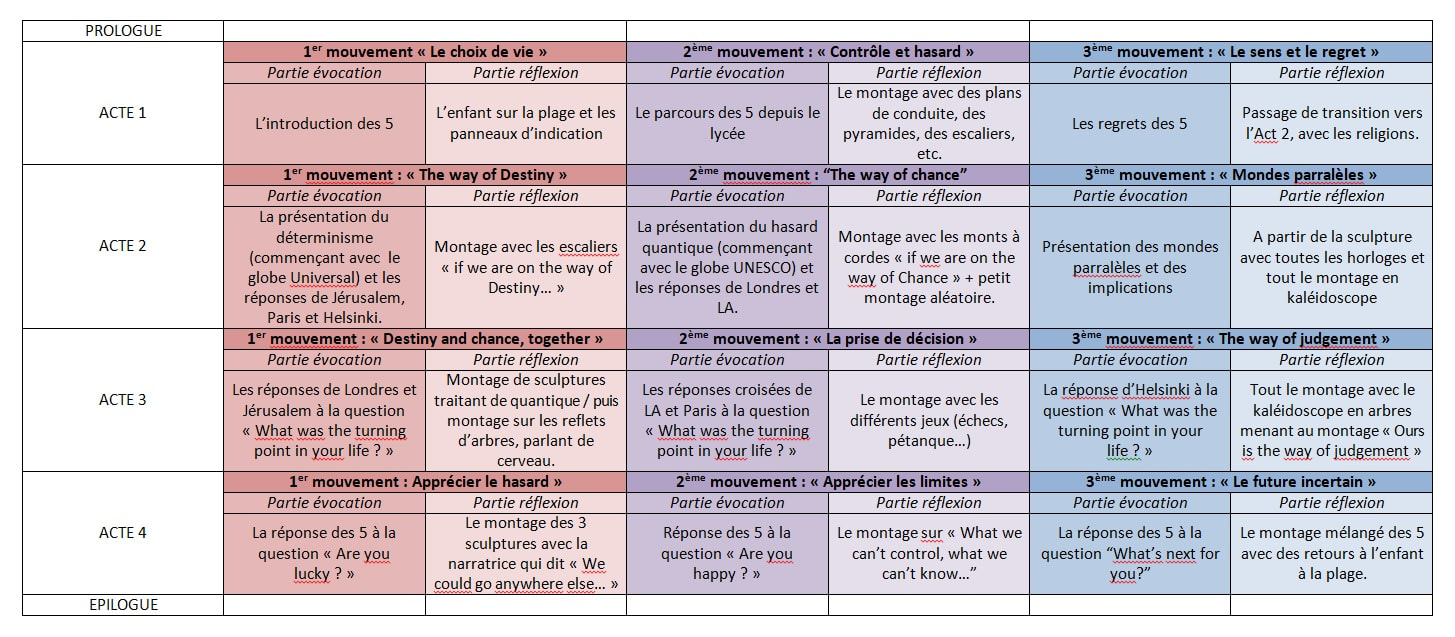

When explaining this to Alexis, I was worried he’d back out of the project. But he didn’t; instead, he doubled-down, said he was fully on-board and readjusted the game plan. He would compose 80% of the music in virtual instruments, and would figure out a way to record the main pieces with real musicians on a tight budget. Around the summer of 2016, he started composing. At first, he jotted down ideas, trying to orchestrate around Paul’s piano music – but there was no real coherence to it all. During this process, I was adamant the music as a whole should have a coherent structure, just like the film. Given that, at face value, the story can be very confusing (many characters and locations, several levels of narration, complicated themes, etc.), the music had to be the cement holding it all together. As we discussed the musical structure, I returned to my massive Word-breakdown of the film and used it as a map for the music: 4 acts, each with 3 movements, each in 2 parts, with the second half of the film mirroring the first. Doing this was extremely beneficial for us both: for my part it allowed me to indicate to him specifically what I wanted, movement by movement; for him, it was a roadmap to explore his creativity while staying on track with regards to the bigger picture. Our process was in place: he would compose a track for each movement of the first two acts, and we would then re-use and adapt them in the second part of the film for the corresponding, mirroring sequences.

|

|

In terms of themes, we initially discussed the idea of having one for each character, but that seemed too confusing. Instead we felt the need to have 3 musical “signatures” that would identify the three core themes of the film: one for The Way of Necessity, one for The Way of Chance and one for The Way of Judgement. Each one would have a distinct musical theme and style (ordered, linear and predictable for Necessity; chaotic, playful and unpredictable for Chance; and a balanced, harmonious combination of both for Judgement). Therefore, the music would reflect the film's theme and mirror the evolution of the story by exploring Necessity (determinism) and Chance (randomness) separately first before putting them together in Judgement (free will).

A few months into the composing though, we came to a stumbling block: Paul’s music. We had originally decided to keep 2 specific piano pieces by Paul at 2 crucial moments in the film and Alexis tried to orchestrate around them. However, it was becoming an issue with regards to the broader coherence of the film’s music. Paul’s two tracks had two very different and distinct melodies, neither of which fitted well into the three main themes we'd established. After some test screenings with friends, we noticed that his two tracks, while beautiful individually, seemed out of place and had become distracting. And so an uncomfortable suspicion that had been growing in my mind confirmed itself: I had to remove Paul’s music from the film. Fortunately, Paul was fully understanding. He conceded that the film would be better served by a single orchestral composer, and the silver lining was that his music would be redirected entirely into the interview series.

From then, Alexis had full creative control over the composition of the original soundtrack and we moved on much quicker. We progressed Act by Act; he would send me a musical movement, I’d edit it in the rough-cut of the film, make adjustments, then write on-screen notes and send it back to him to make further adjustments. By early 2017, Alexis has composed the three most important movements of the film, corresponding to the ends of Acts 2, 3 and 4. These were the musical pieces that we wanted to record with real instruments. At first I was a little worried about how much this would cost. But Alexis had worked several times with an orchestra in Budapest and knew that a bulk recording session for other projects was coming up soon. This was our chance for a low-budget studio recording: Alexis made the right calls and managed to get our film on the last available slot in the studio’s schedule.

On March 4, 2017, I turned 30. The next day, we flew to Budapest. The recording session was on the Monday morning. We had 45 musicians for 3 hours. Honestly, this was a surreal day. The musicians all started showing up in the hour leading up the recording session, taking their seats, discovering the music sheets. First the flute, then the double bass, then the horn, then the violins… I was on the balcony watching them find their marks. Amidst the cacophony of instruments, here and there I could recognize bits of music: a few notes of the Judgement theme by the violin, a little Chance tune on the flute. The chaos grew until 9:29 am when the conductor got on stage: one wave of his wand and it was silence. A second wave and they all harmonized for 20 seconds. And then, a third wave and they started playing the music as thought they’d been honing it for years. The whole thing came to life. I think this was really the first time I became aware that we were making a proper film; until now the whole project still felt like a bunch of friends playing around. Here it hit me that this was bigger than us.

The whole process of composing the music, from my first meeting with Alexis to the last export in July 2017, lasted about 14 months. Once music was all done, we could move ahead with the sound-editing and mixing.

|

[email protected]

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.