Psi

Menu

III - THE INTERVIEWS

Chapter 18

Max Tegmark: One of Many Many Max Tegmarks(Feb 2015)

Max Tegmark: One of Many Many Max Tegmarks(Feb 2015)

|

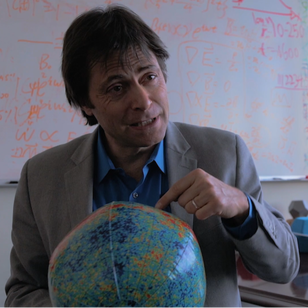

My last interview in Boston was with renowned cosmologist Max Tegmark, professor at MIT as well as scientific director of the Foundational Questions Institute and co-founder of the Future of Life Institute. Alongside Dennett, he is the most recognizable expert I interviewed, having appeared in several documentaries on the BBC, PBS and the Discovery Science channel, and very vocal about the dangers of artificial intelligence alongside Elon Musk and Sam Harris.

The main reason I wanted to interview Tegmark is that he is one of the most prominent and vocal scientists researching and championing the concept of parallel universes. Ever since I was a kid, watching TV shows like Quantum Leap and Sliders, I was fascinated by the idea that there could exist alternate realities where history was different in many interesting aspects. I often found myself wondering what it would be like to travel to them and see what was I was doing there. As I grew older, I took a more focused interest in why such theories existed and broadened my readings to learn about the origins of the universe, with popular science books and shows from Stephen Hawking, Brian Greene or Neil deGrasse Tyson, trying to become familiar the rudimentary basics of physics and cosmology. And that's how I came across Tegmark, in a BAFTA-winning documentary called "Parallel Worlds, Parallel Lives," that follows the lead singer of US rock band Eels, Mark Oliver Everett, on his journey across America to learn about the father he never knew, Hugh Everett, the quantum physicist who devised the theory of parallel universes. As you can imagine, I was very excited when Tegmark originally agreed to meet with me. |

PARALLEL WORLDS, PARALLEL LIVES from EELS on Vimeo.

|

However, I almost never got to meet him and the story of how I eventually secured the interview is one I often remind myself of, because it embodies a mantra I have since tried to stick to more confidently than before: He who dares, wins. This saying originally comes from a popular British sitcom I watched growing up called Only Fools and Horses, and it doesn’t take much explaining: if you don’t try, you don’t succeed, and if you try, more often than not, you will succeed. When I landed in Boston, unlike Doyle and Dennett, Tegmark was yet to settle on a convenient time and place for the interview. To ensure maximum flexibility on my part, I had taken a chance with my flights and booked a whole week in town. I e-mailed Tegmark, called his office, but couldn’t get a reply. I interviewed Doyle, then Dennett, and then three days before leaving, I started to feel like I was just going to have to give up.

But I didn’t want to: I had to have him in my film. And I knew there was one last thing I could try: show up at his office and see if he was there. However, in the moment, two fairly trivial things were holding me back: first, my confidence was lacking. I felt that if he wasn’t answering, it was because he had more important things to do and I didn’t want to be nagging. Second: the weather. That morning, there was four feet of snow in Boston, the record-breaking 2015 blizzard was still going strong, and I had no real motivation to take my equipment, face the elements, the slow-ass subway, find his office on the huge MIT campus and perhaps discover that he wasn’t even there.

Sitting in the hotel lobby, I was debating whether to go or not. It was warm inside, I had a ton of translation work to get done, and it felt like a lost cause. But deep down, I knew it, I was just being lazy. However much I tried to convince myself that going would be a deflating waste of time, my gut kept telling me I was being a chicken. If I did go, there was the off-chance he would be there and say something like: “I have an hour, let’s do it now.” So, after much internal debating, I picked myself up off the couch, got all my equipment ready and headed off into the snow. By the time I got into the MIT astrophysics building, my nose was running, my glasses were steamed-up, my shirt was soaked in sweat under layers of clothes, the bottom of my jeans had frozen and my shoes were leaking puddles – I was seething. But, I found his office on the top floor, and there he was. I caught him as he walked out of his office, we spoke for a couple minutes and, just like that, he offered me an hour to meet with him on the Thursday, a few hours before my flight back to Paris. When I left MIT, I couldn’t care about the weather, and when I got back to my hotel, I imagined seeing my alternate self – the one who had stayed at the hotel instead of taking a chance and going to MIT – sitting on the comfortable couches in the lobby, on his computer, and just thinking to myself: “Sucker!”

When I eventually met with Tegmark, I was introduced to a character who, even more so than Dennett, was beaming with joy, smiling excitedly like a teenager on the first day of summer (I later attributed this to the presence of his wife, Meia, who was sitting in the corner). While setting up the mic, Tegmark put his hand on his heart and belted out a rendition of “La Merseillaise,” the French national anthem. Again, I felt silly having to keep things serious and talk about quantum physics and parallel universes.

To generally introduce what we are talking about with parallel universes, I will quickly recap the different possible ones listed by Tegmark:

Although psi doesn’t specify what kind of reality it is set in, it is more or less navigating the “level three parallel universes,” the ones which most intuitively correspond to the kind of questions the film raises: Do decisions branch out the future? What alternate lives could result from different decisions? Could all possible lives happen in parallel worlds?

In 1957, Hugh Everett, a theoretical physicist at Princeton, tried to resolve the issue of quantum randomness and his theory was popularly illustrated by Erwin Schrödinger’s cat experiment: a cat is put in a box along with a contraption that would be randomly triggered by a quantum event that may or may not happen, but, if it does, will kill the cat. As such, the exact time of death is unpredictable and random, and so as long as the box remains closed, there are chances of finding a dead or live cat. The experiment meant to suggest that quantum mechanics describes the simultaneous and contradictory existence of both: the two possible states of the cat are in fact real, in a state of “superposition,” the probabilities of which are described by a "wavefunction." Both states remain like this until a scientist opens the box to see the result and in doing so, he commits one state to actuality. This event is called the “collapse of the wavefunction,” and is a good illustration of what is widely known as the “observer effect,” i.e. that a conscious observer will affect the nature of reality. Everett tried to explain the paradox by postulating that both outcomes actually happen, each in a different universe: while in our world the scientist observes a dead cat, there is another world which is identical to the first up until that moment where the scientist observes a live cat, and crucially, each world is entirely deterministic. His theory, now known as the “many-worlds interpretation,” ranks as one of the main interpretations of quantum physics to this day - and importantly here, it's the one that Tegmark would put his money on.

As you can imagine, there were so many questions I wanted clarification for and so I tried to pick Tegmark’s brain from different angles. And yet despite my attempt to limit the scope of our 1-hour conversation, there are still parts of his answers that left me with more questions. For instance, the many worlds interpretation made me question what I thought true about the very concept of determinism. Everett’s goal was to provide an account of quantum physics which restored determinism to each individual world. So, if in world A I decide to marry my fiancée and in world B I decide to leave her, despite the appearance that at time T right before the decision I could have gone in two different directions, I was determined to do what I did in world A and determined to do what I did in world B. But how can two worlds, having up until T two identical histories and laws of nature, yield then two different outcomes and yet still be deterministically caused? Doesn’t this completely contradict the whole concept of deterministic causality? I’m sure there’s a simple answer, perhaps even I’m just misunderstanding something basic about the many world theory, but I left Tegmark’s office scratching my head.

|

|

This issue led me to a further concern about personal identity: if we are to believe then that there are an infinite number of parallel universes in which you are at all times deciding contradictory things (leaving/staying, fighting/fleeing, lying/telling the truth, etc.) and thus being many different conceivable beings (a painter, a policeman, a serial killer, a victim, etc. - although the probability of each is more or less high), then how can we even say that they are all alternative versions of “you”? Isn’t there a point where the lump of matter that is “you” in this world is rearranged in such a way that it is no longer “you” in another? Or is one atom a big-enough difference to say it's not "you" anymore?

This comes back to my earlier point about character arcs in storytelling: if after the same past, a character is split in two and each version makes a series of different decisions, how can we say we were dealing with the same person to begin with? If all alternative possible options become reality in some world or another, then doesn’t that in some way void the whole idea of identity? For instance, if in world A I follow my moral motives and decide to stay with my fiancée, but in world B I yield to temptation and decide to leave her, then what does that say of the person I was moments before making the decision? Was I strong or weak in the face of temptation? Was I a man of my word or not? What kind of person was I? You may be thinking: well, that isn’t a question that was settled at that moment, it is precisely through your actions that you form yourself in one way or another and thus create and reveal yourself at the same time to be who you are. I agree with this, but then the “many worlds” interpretation voids this explanation completely, because if we do all possible things in some world or another, then we are essentially everyone at once, and thus no-one in particular. The definition of character comes from early Greek, kharakter, which means a stamping tool, and it carried the early sense of a distinctive mark. The definition of character is thus to be able to describe, to distinguish, to identify – if you could potentially do everything, then you have no character left to be reliably described by. Just like the value of something is proportional to its scarcity, so too with character: if you are the kind of person who could really do both things, then you are less of a particular kind of person, and therefore in a way you have a less defined identity. Scary stuff. |

[email protected]

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.